This is the 2019/20 edition of State of Care

The speed and scale of the pandemic required health and care providers to respond in new ways. The enormity of the challenges they faced meant that, at very short notice, services developed new procedures and ways of working.

In June we published more than 300 examples from the front line of changes that providers had made, so that they could quickly learn from each other and consider whether innovations brought about by the crisis could help shape services in the future.

The examples, from small home care agencies to large acute hospitals, are a celebration of the dedication and resourcefulness of health and care providers and staff. They illustrate their tremendous resilience and imagination, and their determination to think differently to meet the needs of people who use services and keep people safe in a time of crisis.

They included:

- A GP who carried out a virtual ward round to two care homes by video call. She saw every patient in the homes registered on the practice list. She then telephoned the next of kin for each patient to reassure them that their loved ones were being supported.

- Another GP surgery pledged that each member of staff would ring one potentially isolated patient for a chat every day during the pandemic. This good practice was followed by all GP practices in the primary care network.

- A homecare provider has been using tablet computers to record baseline observations of people using its service. Monitoring temperatures and vital signs has helped to identify early signs of infection, enabling them to apply additional social distancing measures and to use consistent care teams to help limit any potential spread of the virus.

- A service for people with a learning disability contacted their favourite local pub to help them create their own pub, while observing social distancing guidelines. The local pub kindly donated items to help make it as authentic as possible.

- An NHS trust introduced a new role of family liaison officer to support patients, their families and loved ones, as well as staff teams. The trust also set up a drop-off and collection station so that people could send items to their loved ones on the wards through the officer.

- A mental health NHS trust set up a 24/7 mental health emergency department with a dedicated phone line for patients in crisis, so that they could avoid acute hospital emergency departments.

Creative thinking to help people understand the dangers of COVID-19

At a care home supporting people living with a learning disability or dementia, one problem staff faced when the pandemic started was how to help residents understand COVID-19 and the changes it was going to make to their everyday lives. The home knew a one-size-fits-all approach would never work, and that true person-centred care would be essential to keep people happy and safe.

The home supported people to do hand washing exercises by adding glitter to the water to represent germs. They found that without soap the glitter sticks to your hands. With soap it all comes off, meaning the germs had gone! People loved doing this, with residents even asking to do it daily for fun.

People were supported to make and decorate hand shapes for the corridors. Every two metres one hand has a piece of coloured cotton wool put on it to represent the germ. This use of visual aids has helped people keep to social distancing guidelines in a safe and engaging way.

One resident had enjoyed the activities at a day service that was no longer running. Rather than let that fall away the manager talked to them and asked, ‘what can we do to help you?’. The solution not only helped that person but the other residents too. They made a weekly timetable to accommodate all the activities of the day centre that staff supported. Some of the quieter residents even got involved and it has made a massive difference to emotional and mental wellbeing.

Some residents still wanted to go out, so staff worked with them to come to an agreement and understanding. Staff accompanied them and showed how to stay safe by using hand gel, staying two metres apart and avoiding busy places.

The provision of health and care services was already changing, but the pandemic has sped up that change. This has happened when groups of people have come together to solve an urgent problem, such as the development of the Nightingale hospitals.

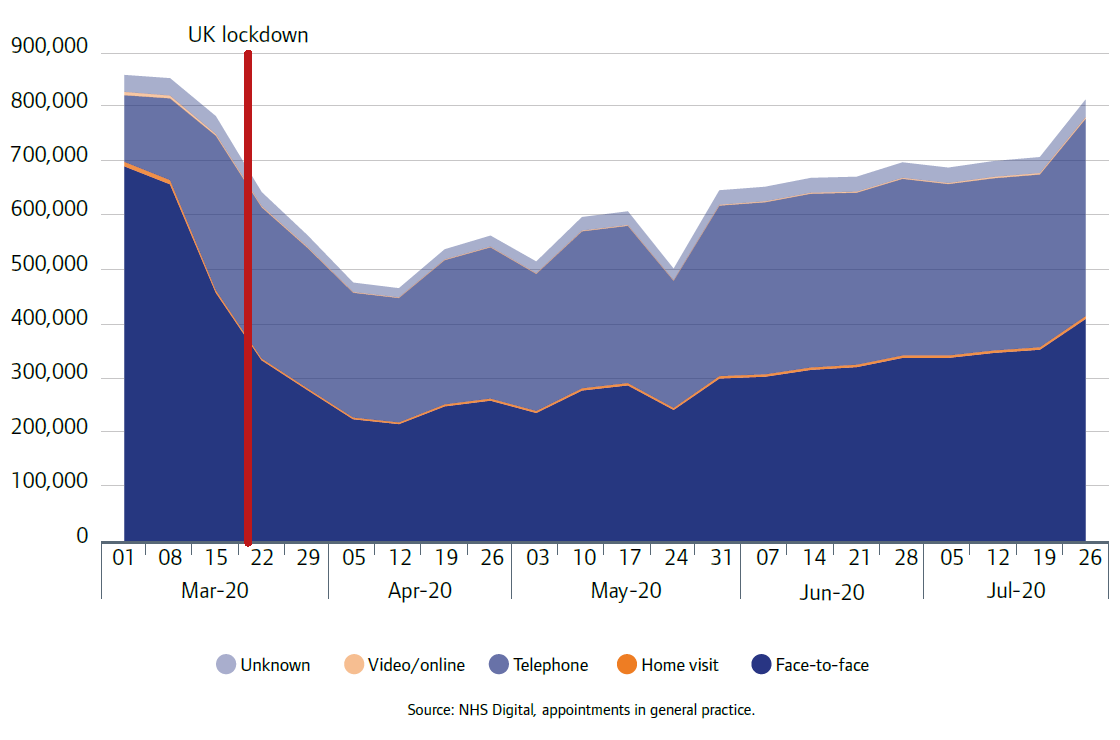

The crisis has also accelerated innovation that had previously proved difficult to mainstream, such as GP practices moving rapidly to remote consultations following the requirement to move to a remote triage-first model of care. In the week beginning Sunday 1 March, 14% of appointments reported to NHS Digital were recorded as being by phone. By the week beginning Sunday 29 March, a week after the lockdown, this had jumped to 46%. It has remained around this figure every week since then (figure 14).

Source: NHS Digital, Appointments in General Practice, March to July 2020

NHSX reported that, by 1 June 2020, 87% of general practices were live with technology to enable online consultations, a figure that has increased markedly during the COVID-19 period. NHSX has also reported that more than two-thirds of practices saw appointments booked online using GP Connect.

GPs have told us they have received positive feedback from patients, and this is generally supported in the surveys we have carried out with people who use services during the pandemic. Most of those who responded to us wanted the access routes available during the pandemic, such as online appointments and telephone and video consultations, to remain available in the future.

However, these remote forms of access were less popular with certain groups, such as people in low-income households, and face-to-face appointments remain important. Healthwatch England heard concerns from people about the accessibility of remote care for people with additional communication needs, as well as people who do not use the internet. They highlighted how digital or telephone appointments and assessments are not always suitable for people living with dementia, autistic people, and those with a learning disability. A recent report from Healthwatch England, National Voices and Traverse, The Doctor Will Zoom You Now, said that, “Key to a successful shift to remote consultations will be understanding which approach is the right one based on individual need and circumstance. A blended offer, including text, phone, video, email and in person would provide the best solution.”

Experiences of using remote consultations during the pandemic

Jennifer had a car crash just before lockdown. She went to the hospital and found she had strained muscles in her neck. The pain got worse so she contacted her GP. She received a phone consultation from a GP the same day she contacted them and was subsequently referred for physiotherapy.

During the pandemic, Jennifer has received GP appointments by telephone and physiotherapy by video consultation. She has mixed feelings about these remote sessions.

She didn’t find the telephone consultations very accessible, and would prefer to see her GP face-to-face, even if this involves a video call. She is only given a five-minute slot for telephone appointments and would like them to be longer. When Jennifer rings the GP for an appointment, she is told she will get a call back that day, but often no time slot is given so it is difficult to plan the rest of her day.

However, Jennifer found the video physiotherapy sessions “absolutely brilliant”, as she did not have to travel to an appointment, which is often difficult when she is in pain. She could see the physio and they could see her to explain exercises. She was given all the information and support she felt she needed. It was also conducted through a very popular app that she is used to using for conversations with her family, so it was instantly familiar. Jennifer thinks she “received better care during COVID-19”, as she “didn’t feel as though as I had been left out by not attending face-to-face appointments”.

Kerri suffers with anxiety and often has panic attacks. She has experience of accessing the GP and a counselling service but since the coronavirus pandemic, everything has moved online.

Although she is used to face-to-face appointments with her GP, she now uses the online chat function on her surgery’s website. Kerri knows that if she uses this, they will get back to her within 24 to 48 hours. She likes to use the chat function as she can tell her story more by writing everything down and she doesn’t forget anything. She thinks they are listening and reading her messages before contacting her, which feels more like a one-to-one service. If she needs medicine, her prescriptions get sent straight to the pharmacy for her to collect.

However, before the pandemic, Kerri explains she could call the GP and get a same day appointment, but using this chat function it takes longer to speak to someone. Kerri has worries about accessing services on a weekend; if she needs to speak to a GP at the weekend, she knows she will have to wait until Monday. “When it gets to the weekend, I feel a bit isolated.”

Kerri’s counsellor now uses standard video apps for consultations. Kerri is quite happy using technology to access services. She likes being able to access services in the comfort of her own home without needing to sit in waiting rooms, especially when she is not feeling well.

Before the pandemic, Kerri would speak to lots of different GPs and counsellors, but since the pandemic started this has changed and now Kerri only speaks to one GP and one counsellor, which she prefers. She likes not having to repeat her story each time. Since appointments have moved online, she has found they have been on time. She had experienced delays when everything was face-to-face.

In initial feedback from conversations we had with GP practices during the pandemic, they said that practice teams have been working well together and more closely in response to the challenges they have faced, which has enhanced people’s working relationships. Practices also indicated that they had received good support and engagement from others to help them manage the pandemic, including clinical commissioning groups and primary care networks.

In terms of the challenges they have faced, a common theme in early feedback was one of information overload, particularly practices struggling with guidance from different sources that was changing or conflicting. Practices have said that going forward, guidance needs to be much better coordinated and streamlined.

Some of the rapid innovations we have seen since the emergence of COVID-19 have been positive for people with protected characteristics. The Think Local Act Personal group has published a number of encouraging case studies of positive responses to the pandemic, available on their website. They include examples from different parts of the health and social care system, aimed at different groups including yoga for disabled people, inclusive digital innovations for people with a learning disability, and new support systems for Black and minority ethnic staff at an NHS trust.

Some innovations, though, have brought to light the need for equality impact assessments to become an integral part of developments in health and social care, even in emergency situations. For example, we were unable to register two proposed Nightingale-style step-down centres for people recovering from COVID-19 because they were unsuitable for many physically disabled people and older people.

It was clear even before the pandemic that digital solutions such as online consultations and triage apps work well for many. However, many of these innovations exclude people who do not have access to a smartphone or computer, and some have been rushed into place during the pandemic. Arrangements and planning for people who are vulnerable to digital exclusion must not be lost in the rush to prioritise innovative and resource-saving online options.

We have worked with other health and care organisations to identify a set of principles that can help enable innovation in health and social care providers. This work was funded by a grant from the £10 million Regulators’ Pioneer Fund launched by the Department for Business, Energy and Industrial Strategy (BEIS) and administered by Innovate UK. These principles will be published in a report in the autumn.

Next page

Part 3: Collaboration between providers

Previous page

This is the 2019/20 edition of State of Care.

Go to the latest State of Care.

Contents

Quality of care before the pandemic

- Quality overall before the pandemic

- Care that is harder to plan for was of poorer quality

- Care services needed to do more to join up

- Adult social care remained very fragile

- Some of the poorest quality services were struggling to make any improvement

- There were significant gaps in access to good quality care

- Deprivation of Liberty Safeguards

- Inequalities in care persisted

The impact of the coronavirus pandemic

- The impact on people

- The impact on health and social care staff

- Infection prevention and control

- The unequal impact of COVID-19

- The impact of COVID-19 on DoLS

- Innovation and the speed of change

Collaboration between providers

- How did care providers collaborate to keep people safe?

- System-wide governance and leadership

- Ensuring sufficient health and care skills where they were needed

- The impact of digital solutions and technology