This is the 2019/20 edition of State of Care

During February and March 2020, COVID-19 emerged as one of the greatest public health crises that the UK has faced for 100 years. In the space of a few short months, the pandemic placed the severest of challenges on the whole health and care system in England. A crisis so widespread and fast in its impact was always going to test the resilience and responsiveness of the system like never before.

In this report, written as we started to leave the initial crisis phase of the pandemic and begin to think about how we learn to live with the virus for some time to come, our focus is on the impact it has had on health and adult social care services, their staff and the people using them. We do not consider the overall handling of the pandemic itself. However, at a time of rapid response, we take the opportunity to emphasise the learning and improvement that has taken place across the system.

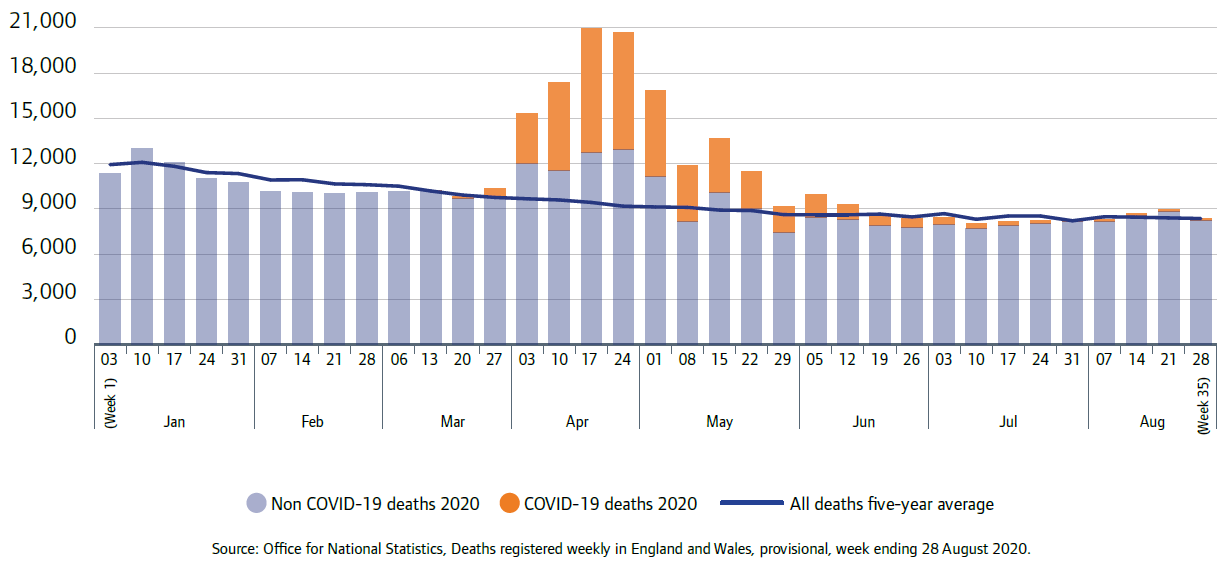

The impact of the pandemic was starkly shown through the tragic increase in deaths in April, May and June. As well as the deaths from confirmed or suspected COVID-19, there appears to have been an increase in other deaths compared with the average of the last five years (figure 7). Deaths overall had returned to their average rates by the end of June.

Source: Office for National Statistics

Week 35 is the week ending 28 August 2020

For people receiving care in adult social care services, the pandemic has been particularly severe. The Office for National Statistics published a report in July that highlighted the particular impact of COVID-19 on people in care homes. The number of deaths of care home residents occurring in England and Wales from 28 December 2019 to 12 June 2020 (registered up to 20 June 2020) was 93,475; this was 29,393 more than the same period last year, a 46% increase. Of these deaths, 19,394 mentioned "novel coronavirus (COVID-19)", which was 21% of all deaths of care home residents.

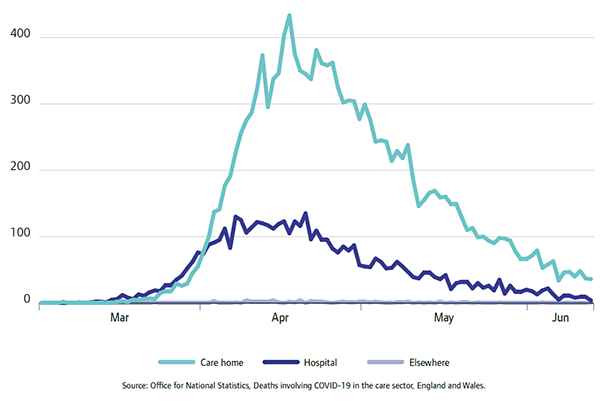

At the beginning of the pandemic, more deaths involving COVID-19 among care home residents occurred in a hospital setting; but from the beginning of April, deaths of residents in the care homes increased more rapidly, becoming much more prevalent and highlighting the terrible burden that care homes faced (figure 8).

Source: Office for National Statistics

The Office for National Statistics also reported that the decline in COVID-19 mortality from mid-June brought weekly deaths in hospitals and care homes down to average levels. However, deaths in private homes remained at 30% to 40% above what would normally be seen. Over the course of the pandemic as a whole, the proportion of deaths occurring in hospitals has been lower compared with the same period in previous years (40% versus 47%). The proportions of deaths occurring in care homes and private homes increased.

The virus has had a disproportionate impact on care for older people. Very quickly, care homes stopped visits from family and friends to try and control the virus, which prevented a crucial source of emotional support for older people. Measures in place to try and prevent the spread of the virus within homes had a huge impact on people, with some residents confined to their rooms, social events cancelled, and shared areas in the home – such as dining rooms and lounges – closed due to physical distancing.

Relatives were worried about how their older relative receiving care would cope without the regular support of friends and family, and the impact on people not being able to visit partners or spouses during lockdown has increased loneliness and stress.

Adult social care providers and staff have had to balance the priority of reducing the risk of COVID-19 transmission in services with the importance of maintaining a focus on the needs and rights of individuals in their care. Many services have used creative solutions to maintain social contact while still observing physical distancing, as shown in the care home example below.

Maintaining safe social contact during lockdown

We spoke to Sarah, whose mother, Lesley, has Alzheimer’s disease and lives in a specialist dementia unit at a care home. Lesley is cared for by specialist nurses and care assistants, as well as support from a dementia consultant several times a year and her GP when needed. Sarah and other family members used to visit Lesley frequently, and they feel that Lesley is happy in her home and receives good care from the friendly and helpful staff.

Earlier this year, the home where Lesley lives had some cases of COVID-19, and decided to go into lockdown before the official government advice came out. Sarah was supportive of this, although it meant she was no longer able to visit her mother, because she understood the actions were being taken to keep people safe.

Sarah and her family called the home every day to check how Lesley was doing, and the staff were always happy to provide an update and support Lesley to speak to her family directly over the phone. When it became clear that lockdown was going to last for a longer period, the care home arranged for video calling between the family and Lesley, and supported Lesley to use this. The staff noticed that Lesley would offer her family tea and cake over the video call, and suggested to Sarah that they arrange to call at teatime, so they could all have tea and cake together. They arranged a special tea at Easter, and decorated an Easter bonnet for Lesley to wear.

When lockdown measures started to ease, the care home arranged for garden visits so that Sarah and other family members could see Lesley in person. Staff made sure that safety measures were in place, such as providing gloves and masks, allowing one visitor at a time, and keeping to physical distancing advice.

During lockdown, Lesley’s consultant from the hospital was able to carry out her quarterly assessment by video-link, and later commented that he was impressed with how well the staff knew Lesley’s condition and the level of detail they were able to provide.

Sarah told us that she “could not fault the care that [Lesley] had been given by the staff pre and during COVID”. She is fully confident and it helps to know that her mother is being so well cared for in these difficult times.

Some homecare services faced a significant challenge in maintaining continuity of care for the people they looked after. Our first COVID-19 Insight report highlighted that, in early May, agencies that submitted data to our tracking survey had on average 9% of their staff absent because of the impact of the coronavirus.

Some homecare staff responded to the COVID restrictions by introducing new ways to keep people safe during the pandemic, while maintaining contact with their loved ones – for example by sending videos, photos and regular, reassuring emails to family members through the registered manager. Staff at another homecare agency delivered letters from pupils at a local primary school. One recipient said, "I started the day feeling really fed up, but when my letter arrived, it really brightened my day and I now look forward to writing back.”

A forthcoming report by the Think Local Act Personal Insight Group, which has key partners from across the social care and support sector (including CQC), highlights the importance of good communication and willingness to engage with people and families, together with a commitment to maintain personalised approaches to care and support.

Mental health care

The pandemic has had a significant impact on many people’s mental health and wellbeing. Healthwatch England highlighted what they had heard from people about the negative impact – loneliness and social isolation, bereavement, employment and financial stress, and anxiety about their health all played a part. Some autistic people were feeling more anxious due to not being able to follow their usual routines. Healthwatch England described the effect that the reduction in services had on people, and that people wanted more regular, consistent support by phone or face-to-face contact – particularly if they were close to crisis point.

For people with severe mental health conditions, we have seen examples where COVID-19 has resulted in delayed discharges into community placements, and also of community placements no longer being available, for example care homes and residential schools being closed to admissions.

There was an increase in calls to CQC’s helpline about, or from, people detained under the Mental Health Act – often expressing distress or confusion about why people were more likely to be confined to their rooms rather than being able to move around freely. Of the eight mental health services we inspected by mid-June since pausing routine inspections, five were as a direct result of concerns raised with us by staff or members of the public.

From our monitoring carried out since the start of the pandemic, we have found some examples of mental health providers giving good support to their patients. These include:

- Helping people to access family and friends and informal support networks, by providing them with digital devices for video calling and contact. Patients have been very appreciative of this where it has been done well.

- Providers proactively arranging for advocacy services to be brought into wards in a remote way, for example by ‘walking’ an advocate round a ward on a tablet screen to engage patients ‘on the spot’. Some face-to-face advocacy meetings are now taking place.

- Providers arranging remote contact with other support services, for example interpreters.

- Providers arranging for family members to be involved in care planning meetings.

In hospitals, we saw examples of patients’ leave being cancelled or restrictions placed on their movements, as well as limits on visits from friends and family, in line with government COVID-19 advice. Cancelled leave and restrictions on movements, including visits from loved ones, can increase the risk of closed cultures developing.

We have seen examples of services managing this challenge well, with increased mobile phone access and the use of video calling. However, some patients have expressed concern that restrictions on communicating with families will increase once the crisis is over. We will continue to work with services to challenge any increase in restrictions.

Reduction in healthcare activity

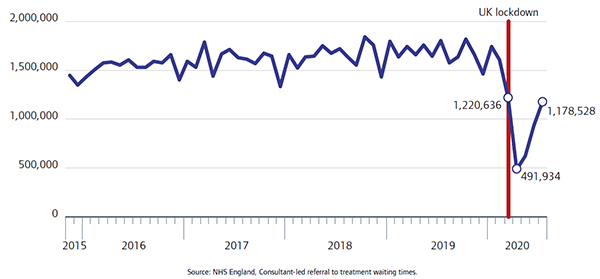

At the beginning of the pandemic, there was a substantial drop in the number of new referrals to treatment (figure 9), falling from 1.6 million in February 2020 to less than 500,000 in April, a fall of 69%. Since then, the number of new referrals has risen each month, reaching almost 1.2 million in July.

In addition, the length of time that patients were waiting for a diagnostic test rose sharply. At the end of May, more than 571,000 patients (58% of the waiting list) were waiting at least six weeks for a diagnostic test. This was a substantial increase since the end of March, when 10% were waiting at least six weeks.

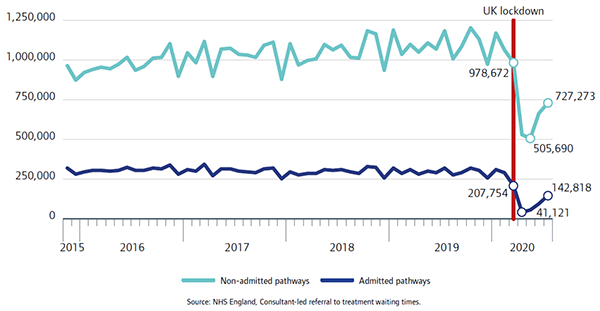

At the same time, treatment for patients also fell substantially: the number of admitted patients starting treatment fell to just over 41,000 in April 2020, while for patients on non-admitted pathways the number starting treatment fell to a low point of just over 505,000 in May. In both instances these were the lowest they had been since at least April 2015, although activity has subsequently recovered somewhat (figure 10).

As a result, the length of time that patients were waiting for treatment increased substantially. The proportion of patients who had been on the waiting list for more than 18 weeks increased by 36 percentage points between February and July 2020.

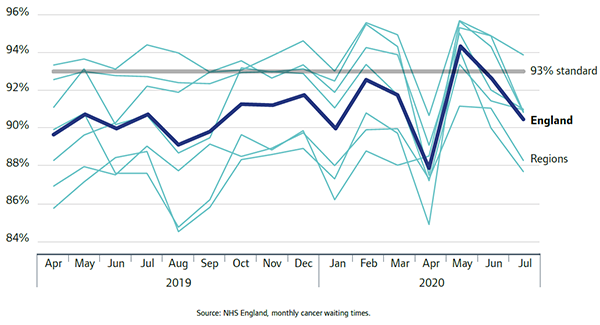

Cancer services were significantly affected. There was a 58% fall in the number of cancer referrals to acute trusts in April 2020 compared with April 2019. And despite the fall in referrals, the proportion of people seen within two weeks of referral also fell sharply, with no region meeting the 93% standard in April 2020 (figure 11), although there has been some recovery since then.

However, for those already with a cancer diagnosis, the rate at which patients started treatment within the target 31-day period was largely maintained.

In June 2020 Cancer Research UK highlighted the impact of pausing cancer screening, noting the increasing backlog. At 10 weeks after the introduction of lockdown, they estimated there were 2.1 million people waiting for breast, bowel or cervical screening. Delays in screening reduces opportunities to detect cancers at an early stage, and increases risk for people.

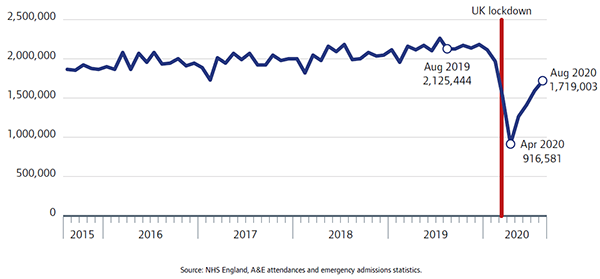

We saw a similar decline in people accessing urgent and emergency care, with 57% fewer people attending urgent and emergency care in April 2020 than in April 2019. Since then, attendances have started to rise again, by August reaching more than 1.7 million (up from just over 0.9 million in April), but this was still 19% lower than 12 months previously (figure 12).

Urgent primary medical care services

The pandemic has raised significant challenges for urgent primary medical care services, such as NHS 111, urgent treatment centres and out-of-hours services. Similar to other services, they had to adopt strict infection prevention and control measures to protect staff and people who use services, including the need to socially distance. Many staff switched to working remotely, where possible, to ensure that people can continue to receive safe and effective services. To support this, leaders have provided them with the appropriate technology and training.

There was a large spike in demand at the start of the pandemic – more than a million extra calls to NHS 111 in England – in response to the public campaign to highlight the need to contact 111 first with any concerns. Calls almost doubled in March compared with preceding months, before falling back to more normal levels in April. To keep up with demand, providers of NHS 111 had to speedily recruit and train new staff, including call handlers, which often meant bringing staff offline to support training. This then led to a build-up of calls. Additional staff were mostly staff redeployed from other parts of services, which meant that once the crisis was over, and demand returned to pre-COVID levels, many services lost this additional resource.

We know that during the early stages of the pandemic, there was a lot of confusion surrounding many health and care services and how and when people should access them. We have also heard of examples of people needing an urgent primary care service being passed around different services or unclear of who to contact to get the care they needed – many of whom were people who did not show COVID-19 symptoms but needed care for other urgent illnesses.

Inpatient survey

We commissioned a survey of hospital inpatients to find out about their experiences during April and May of 2020, when the first wave of the pandemic was at its height. Overall, most patients reported positive experiences of care, as has been found in previous adult inpatient surveys.

Most patients overall (83%) said they felt safe from the risk of catching COVID-19 in hospital, though those who were diagnosed while in hospital were the group who felt least safe (68%), when compared with those who did not receive a COVID diagnosis (84%).

Perhaps unsurprisingly, people with COVID while in hospital reported consistently poorer experiences than those who didn't have COVID. The most pronounced differences were during discharge and when thinking about care after leaving hospital. When leaving hospital, 33% of people with COVID did not know what would happen next with care, compared with 18% for people without COVID. Of those discharged to a care home, 37% said they did not know what would happen next with their care after leaving hospital, up from 25% in 2019. Higher rates were also seen for those with a learning disability or a mental health condition.

Oldest patients (75+) were much less likely than other age groups to say they kept in touch with family and friends while in hospital. Patients with pre-existing long-term conditions, those with Alzheimer’s, or who were blind or partially sighted said they were also less likely to have kept in touch with others.

Dental care

At the end of March, dental practices were advised to suspend all routine treatment, as part of plans to prevent the spread of coronavirus. NHS regions were instructed to set up local urgent dental care centres to help people with emergency dental problems. This caused access problems nationally. Some areas were quick to respond due to already well-established system relationships; others took more time. Some dental practices provided care in the absence of urgent dental centres.

Healthwatch England has highlighted how, while routine appointments were on hold, people did not know how to access emergency dental care – causing them stress while experiencing acute dental pain or other serious symptoms. In June, as dental practices started to reopen for routine appointments, they heard that the information being provided from some services was inconsistent or confusing, leaving people unsure about whether they were running again, and what treatment would be available.

Dental practices have needed to modify their methods of delivering care to account for the need of social distancing and enhanced PPE for staff. Following some clinical procedures, the treatment room has to be left ‘fallow’ before cleaning to reduce the risk of transmission of COVID-19. This has resulted in a large reduction in treatment capacity for practices and it is likely to be some time before full capacity is reached.

Community health services

At the start of the pandemic, many community health services quickly adapted their delivery model to offer access to services by telephone, video or internet to ensure that access could be maintained. For example, sexual health services moved to a booked online service and this received positive feedback from people using services and health professionals.

District and community nursing teams have also explored options for working remotely but there is a need to be mindful that this may not work for everyone. This is particularly apparent in services for children and young people where reduced contact with families has led to a concerning decrease in referrals for support. Redeployment of staff in these services to support the pandemic response also increased the case load for health visitors and this has impacted on the ability of community health services for children to provide safe and effective care.

Community health services are likely to be a key player in supporting the COVID recovery. While there is a strong emphasis on rehabilitation in the community, community hubs and cross-sector multi-disciplinary team working, the challenge for the workforce will be to manage the complexity of COVID rehabilitation while at the same time restarting discontinued services, dealing with a backlog of non-COVID cases, and not suffering poor health as a result of increased workload.

Services for children and young people

The pandemic caused disruption and changes to healthcare provision and access to services for children, young people and families. Services responded rapidly, aiming to balance requirements for continued provision with the call to support the broader health and care system. The full and long-term impact of responses and arrangements for children and young people are yet to be fully understood.

Children and young people presented less frequently to the urgent and emergency healthcare system compared with pre-pandemic times. This meant that those children and young people who did attend for emergency care were more acutely unwell at the time of presentation than might have previously been expected. Some acute services diverted children and young people from emergency departments to be assessed in the children’s ward.

There was a substantial reduction in referrals for mental health services at the start of the pandemic (the number in April 2020 was 41% lower than in April 2019). The low referral rate is a likely consequence of children not attending GPs, school or accessing school nurses, who are the primary referrers (indeed, the number of referrals from primary healthcare fell by 63%). The reduction in activity is likely to lead to longer waiting times for assessments and specialist interventions, including access to inpatient beds, as services work to catch up. Until the long-term impact of reduced or delayed referrals is understood, there remains a risk that children may be suffering without support and experience further deterioration in their mental health.

School-based immunisations were suspended due to school closures for most children. While the programme has restarted, the full recovery timeline for the immunisation programme remains a challenge. Access to other areas of routine care proved a challenge for families, for example healthy child programme screening and access to dental care.

The absence of school for the majority of children and young people meant many were not able to access support services provided only through school. This was a concern for families of children and young people with complex health care needs, special educational needs and disability. Service provision was already varied across local areas. Reduced support resulted in increased pressure on families to meet those complex health and care requirements without their usual levels of support. Families and educational settings also struggled to access the necessary supplies for the provision of complex care, where responses to the pandemic had seen shortages for the system. We also heard that access to ongoing therapy interventions and support was difficult for families, as a result of the deployment of therapy professionals to other areas of the system response.

Accelerated digital approaches across the health system meant that children, young people and families were able to access virtual appointments and assessments. However, the drive for digital approaches, coupled with less contact with system-wide professionals and a reduction in the number of referrals for support seen at the peak of lockdown, means that there is a risk that not all children and young people were protected from harm through the crisis.

Next page

The impact on health and social care staff

Previous page

This is the 2019/20 edition of State of Care.

Go to the latest State of Care.

Contents

Quality of care before the pandemic

- Quality overall before the pandemic

- Care that is harder to plan for was of poorer quality

- Care services needed to do more to join up

- Adult social care remained very fragile

- Some of the poorest quality services were struggling to make any improvement

- There were significant gaps in access to good quality care

- Deprivation of Liberty Safeguards

- Inequalities in care persisted

The impact of the coronavirus pandemic

- The impact on people

- The impact on health and social care staff

- Infection prevention and control

- The unequal impact of COVID-19

- The impact of COVID-19 on DoLS

- Innovation and the speed of change

Collaboration between providers

- How did care providers collaborate to keep people safe?

- System-wide governance and leadership

- Ensuring sufficient health and care skills where they were needed

- The impact of digital solutions and technology