We looked at cancer care in 8 areas of England in March and April 2021. This was when services were under the severe pressure associated with the second wave of COVID-19.

This report is part of our series of provider collaboration reviews.

These reviews aim to show the best of innovation across systems under pressure, and to drive system, regional and national learning and improvement. We also look at how local systems are managing services during the pandemic and reflect some of their main concerns.

Cancer care is provided by a wide range of services, including NHS hospitals, GPs, adult social care, hospices, 111, GP out-of-hours services and community pharmacies.

The local areas or specific organisations covered in our reviews were:

- Leicester, Leicestershire and Rutland sustainability and transformation partnership (STP)

- Cambridge and Peterborough STP

- Shropshire, Telford and Wrekin STP

- Our Dorset

- South West London Health and Care Partnership

- Bath and North East Somerset, Swindon and Wiltshire Partnership

- Greater Manchester Health and Social Care Partnership

- Surrey Heartlands Health and Care Partnership

At the time of our review, some of these areas were integrated care systems (ICS) and others were sustainability and transformation partnerships (STP). We wanted to know whether people were getting the right care at the right time and in the right place, and how collaboration across local areas had made a difference. Our information also includes responses from people who were receiving cancer care.

Much of the joined-up work is usually behind the scenes from the patient’s perspective, especially where we have heard about the importance of cancer alliances in local systems. We have seen in the past how good collaboration is often evident in the better examples of care we find and people’s experience of care.

This report shares the overall learning from the review, which falls broadly into the following themes:

- Local systems have collaborated in different ways to try to ensure people’s continued access to cancer services.

- Local systems continued to make personalised care a priority despite the pandemic, but improving communications about people’s changing care pathways was vital.

- Collaboration occurred between providers locally to make sure that they had definitive lists of the most vulnerable people.

- Established integrated care systems were able to adapt their governance structures in response to the pandemic so they could make quicker decisions and help deliver cancer services.

- Systems have used redeployment and upskilling initiatives to make sure cancer services were maintained where possible, but in some places, redeployments may have adversely affected cancer services.

- Local systems focused on rapid improvements to online solutions – there were some innovative approaches with good outcomes for providers and patients, but online consultations are not ideal for some consultations and attempted diagnoses.

Looking forward, we have identified in this review the following common challenges for local systems:

- Working together to ensure timely access to cancer services for early diagnosis, treatment and ongoing care.

- Fears around catching COVID-19 meant that some people haven’t sought medical help. This has been exacerbated by differences in national and local messaging about seeking healthcare advice.

- There is a risk of widening inequalities among cancer patients stemming from an absence of system-wide strategy, and challenges around the capturing and sharing of people’s demographic data. This could be made worse for people without access to digital technology and those who struggle to travel to centralised hubs.

- It is vital that all key system players, especially adult social care providers, are involved in planning system-wide approaches to cancer care.

- There are fears of workforce burnout and concerns around workforce capacity to address the backlog of people needing cancer care.

The evidence in this review

As part of our review we carried out these activities:

- Remote access to electronic patient records / management computer systems with consent from general practices.

- Worked with voluntary partners to understand the experiences and views of people using services through a short survey.

- Remote interviews and focus groups with services across eight local systems.

- Analysis of available information around local systems, comprising demographic data, inequalities data, COVID-19 outbreak analysis, and cancer data from NHS England, as well as a review of CQC’s information.

1. Ensuring access

Key points

- Local systems have collaborated in different ways to try to ensure people’s continued access to cancer services.

- While access to cancer care in the pandemic has been different for many people, some people have struggled more than others to get the care they needed.

- Changes in the way people accessed care, to reduce the risk of COVID-19 exposure, were sometimes successful – virtual appointments have worked well for some people but not everyone.

There were several challenges during the COVID-19 pandemic resulting in concerns about people’s access to cancer care. Capacity issues posed significant problems for people trying to access services.

The patient journey, including screening, diagnosis and treatment, were all affected by reduced capacities and sometimes the availability of medicines was also impacted. Additionally, we heard that people appeared to be less likely to contact medical professionals if they experienced cancer symptoms, which potentially led to diagnoses of cancer at later stages.

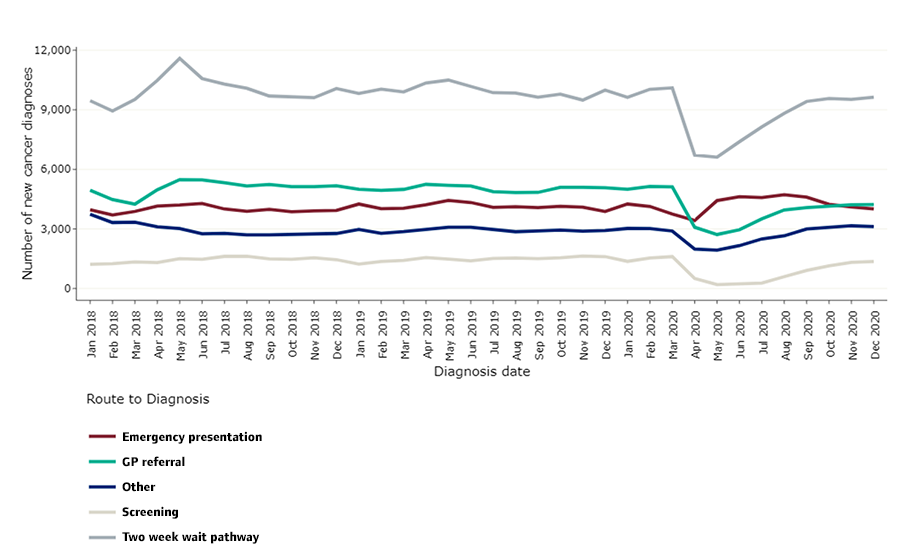

There was a decrease in diagnoses of cancer via screening, GP referral and the two-week wait pathway from April 2020 (figure 1). This is reflected in the increase in emergency presentations in the early months of the pandemic.

On review of 98 GP case records, we found that 4% of patients had evidence of delay in referrals being made. We saw that 54% of the 98 patient records showed a physical examination before a referral to secondary care. People who were not examined were mainly presenting with symptoms of lower gastrointestinal tract and prostate cancer.

Although some patients may not have required a physical examination to satisfy referral criteria to cancer pathways, a lack of physical examination at initial consultation can sometimes contribute to missing later signs of cancer for some people. This may have also contributed to an increase in emergency presentations of cancer we have heard about in this review.

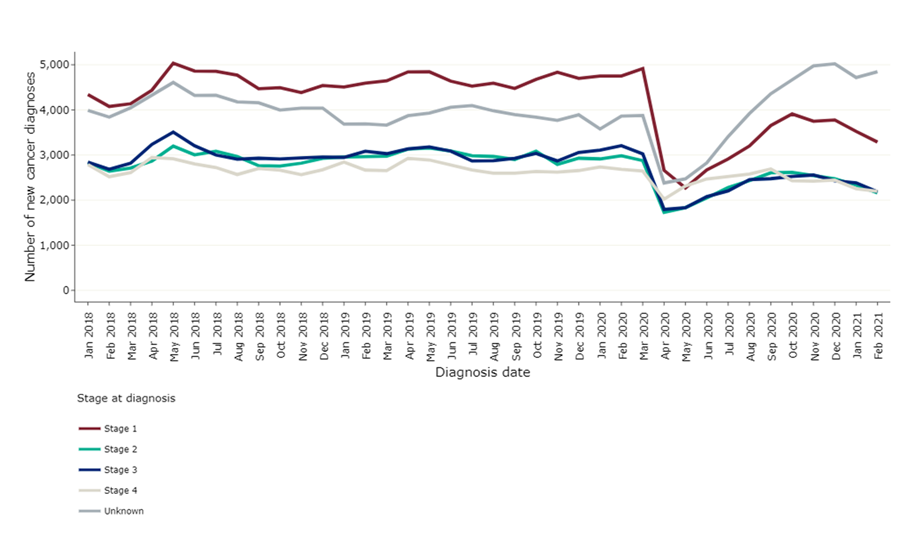

There has also been a significant drop in cancer diagnoses detected in the early stages (stage 1 and 2) and an increase in cancers detected in stage 4 in the early months of the pandemic (figure 2). Despite this increase in stage 4 cancer diagnoses, this was still fewer than total pre-pandemic levels.

Systems have reported that people were fearful of COVID-19 and felt uncomfortable visiting hospitals and clinical settings. As a result, some patients delayed or deferred appointments altogether – this may have resulted in the subsequent increase to later stage diagnoses that have been recorded.

This work has been produced by the National Disease Registration Service

This work has been produced by the National Disease Registration Service

We heard that waiting times have been a source of concern during the pandemic and there have been increasing backlogs in diagnostics and treatment services. There was a decrease in the number of people seen or treated against the three waiting time standards (two-week-wait, 31-day wait, 62-day wait). In the time period April-February 2019-2021 and April-February 2020-2021, there was a 16% (356,893 referrals), 15% (42,228 fewer people) and 13% (19,068 fewer people) reduction in people being referred or treated as per the respective waiting time targets.

We have seen that the numbers of people seen and/or treated had partially recovered by February 2021 but were below those seen pre-pandemic. Two-week waits seem to have recovered quite well, and data suggests that numbers in March 2021 exceed those of February 2020. It suggests that some patients who had perhaps not presented earlier in the pandemic are feeling more comfortable to come forward or may have had more severe symptoms prompting a medical review.

In response to concerns about fewer people presenting with symptoms suggestive of cancer, we heard that many systems had responded with communication campaigns, individually as well as part of nationally driven moves. There were strategies to increase people’s awareness and willingness to seek advice.

This contrasted with strict national messaging advising people to ‘stay at home’. We heard this was sometimes confusing for people who use services. Some people were unsure whether they should attend screening appointments, and so did not book appointments when invited or did not attend hospital appointments, citing mixed messaging around shielding.

Several systems used local and social media to reach people, for example local radio. We heard how one system used targeted communications campaigns to contact specific groups where they noticed additional barriers to accessing care. Despite these positive examples, we heard that some less publicly familiar cancers, like head and neck, were sometimes missed in the messaging and there was less awareness about certain symptoms.

Changes in care provision and pathways

Alongside communication campaigns, all systems in our review also redeveloped and adapted patient pathways to enable better access. In some cases, we heard this decision-making was centralised to ensure equitable access for patients based on priority scores rather than their locality. Local cancer alliances were involved in some cancer hubs (dedicated COVID-19 free sites which coordinate cancer care) and they tended to take a leadership role to reduce inefficiencies in communication between services.

In Greater Manchester, for example, the cancer hub oversaw and coordinated a system-wide queue for diagnostics and treatment, ensuring equitable access for people as demand and capacity were matched across the system.

However, in a different system, we heard that sometimes these new pathways were more difficult to navigate, and we heard that GPs were occasionally unsure who to contact if further support was required.

Other changes in patient pathways involved adapted diagnostics and treatments to help reduce hospital attendances and potential exposure to COVID-19. Systems reported other initiatives such as improving the use of community diagnostic hubs to encourage diagnostics away from hospital settings, but also using different medical techniques to minimise aerosol generating procedures (which produce respiratory droplets that can be airborne and spread infection).

These included the use of computed tomography (CT) colonography and capsule endoscopy instead of colonoscopy. In some cases, this may have meant that more people could be tested.

Cancer treatment plans were also changed, with chemotherapy being the most affected. These changes were mainly adopted from NICE Guidance (NG161), which was quickly developed using advice from specialist multidisciplinary teams. We heard several examples of how chemotherapy was managed so that some people did not need to attend hospital as frequently. Some examples include:

- having longer intervals between administering chemotherapy

- using immunotherapy instead of chemotherapy to avoid immunosuppression

- switching to oral and subcutaneous chemotherapy in favour of intravenous so that treatment could be delivered at home

- encouraging more use of chemotherapy or radiotherapy before surgery

- pausing treatment according to risk assessments

- teaching patients to self-administer appropriate medicines

- increasing the use of prophylactic medicines to prevent specific causes of sepsis, to stop further admission to hospital.

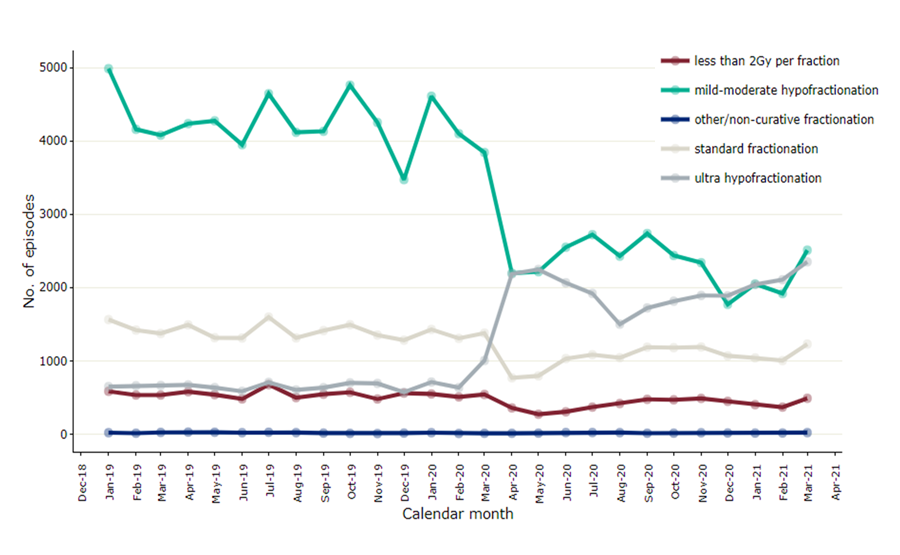

The number of patients receiving systemic anticancer therapy (chemotherapy) dropped at the onset of the pandemic (figure 3). Monthly activity in April and May 2020 represented only 82% and 74% of the activity that was carried out at the same times in 2019, suggesting that monthly activity continued to be below pre-pandemic levels.

There was also considerable drop in curative radiotherapy episodes (figure 4) with a preference to give larger doses over a shorter period (ultra hypofractionation) to reduce hospital attendances.

This work has been produced by the National Disease Registration Service

This work has been produced by the National Disease Registration Service

Systems used new ways to make cancer care more accessible for patients during the pandemic to keep them safe. One of the key adaptations was providing cancer care at home. This included services such as phlebotomy, chemotherapy treatment, pharmacy delivery, hospice care as well as virtual consultations and ward round.

We heard about a range of initiatives to ensure patients could receive their medicines. Drive-through medicines pick-up services and home delivery services were established. Volunteers were used to meet demand in some cases.

We also heard about satellite and outreach services that were used to provide further support. There was greater use of homecare services and mobile chemotherapy units, where a nurse was required to administer the medicine if the patient was unable or reluctant to attend hospital.

In Leicester, Leicestershire and Rutland we heard that the clinical commissioning group (CCG) expanded the provision of chemotherapy at home to reduce the number of people needing to attend hospital premises and ensure they would continue with their treatment at home. However, in some other areas, we heard that funding for home services did not extend to patients living on the outskirts of the system and therefore impacted on where they could receive care.

We also heard that community provision of care was being made more accessible. This included drive-through phlebotomy and medicine services, diagnostic imaging in a hospital’s car park, chemotherapy buses and an oncology transport service to protect patients who were having treatment.

A good example was Cambridge University Hospital, which set up a blood testing facility at the local park and ride centre. This allowed patients to get their blood tests without entering the hospital. We heard how the trust aimed to set up further hubs and to expand blood testing in patients’ homes for those who were unable to travel or live remotely.

We heard that one of the major enabling factors in the delivery of effective community care was the increased use of digital solutions to reduce in-person attendances. We heard about providers offering virtual consultations and virtual ward rounds to attend to people using their services. Although there were some concerns about addressing safeguarding issues remotely, these were addressed using video clinics. One person reported:

“I had no problems taking part in this virtual consultation and it was just as good as a face-to-face consultation… as my blood test was processed beforehand as normal, the only difference was there was no physical examination performed.”

From what we heard, the implementation of virtual appointments seems to have increased some people’s ability to access cancer services (see Use of technology) but it was not necessarily good for everybody. Digital solutions enabled vulnerable staff to work from home, allowing them to continue contributing to service provision. When hospital attendance was unavoidable, providers worked together to make wards as safe as possible (see Keeping people safe).

2. Personalised care

Key points

- Local systems continued to make personalised care a priority despite the pandemic, but improving communications about people’s changing care pathways was vital.

- There are good examples of the way local systems shared personalised care plans.

- Online consultations worked well for some people, but some other aspects of care, such as wellbeing services, sometimes came to a halt.

Achieving the national cancer priority of ensuring that people receive personalised cancer care was one of the key challenges during the pandemic. We heard that anxieties around attending healthcare settings and a reduction in face-to-face appointments were key barriers in providing personalised care and systems had to adapt to meet these challenges. This was further exacerbated by limited capacities due to stretched services.

We heard how visiting restrictions caused distress for both people using services and for their families and loved ones. As with many other kinds of healthcare, digital solutions were heavily relied upon to adapt and support personalised care (see Use of technology).

Despite these issues, most systems we reviewed reported that maintaining personalised care was a priority during the pandemic and some highlighted their initiatives and actions.

We heard of collaboration between a variety of partners including charities, local authorities and acute trusts. For example, in Leicester, Leicestershire and Rutland a local hospice used the same patient information system as most GPs in the area and was able to share personalised care plans.

From South West London and in Dorset, we heard about efforts to increase people’s participation in making decisions about their care via patients and patient groups, in order to inform planning of services. And we heard how some systems supported families in delivering care themselves to their loved ones.

In Bath and North East Somerset, Swindon and Wiltshire, staff in one hospice trained families and carers on how to administer some medicines so that people could receive care at home without added risk of COVID-19 exposure from healthcare professionals’ visits. We heard that this new way of working may have allayed some people’s anxieties and promoted treatment uptake in the wider population.

Virtual or telephone consultations were set up for medicines advice. We heard that some patients preferred a face-to-face appointment and as a result a blended approach was taken. This ensured patient choice was considered and patients had access to medicines advice through several routes.

People have told us about their recent cancer care, and this is one example of experience:

“I felt fully involved in all decision-making and had good opportunities to discuss directly with my consultants as well as great nurse and technician back-up. Everyone has gone the extra mile to help set this up in the best possible way. I feel there are some options still open even as we begin treatment. For instance I will start with hospital appointments for the first cycle, but if I am willing and manage it I will be able to self-administer some things from then on, but it has been made clear that we can discuss different handling if I find that difficult and that the chemo timetable and results will be carefully reviewed as we go along with frequent phone consultation.”

Systems told us they recognised the need for more communication with people using services because of patient pathway redesigns. In many areas, cancer care navigators or cancer specialist nurses were employed to support people throughout their cancer journey. Although this was a system in place before the pandemic, this role was key to monitoring people’s wellbeing and helping them navigate the new ways of working.

We heard how some providers introduced hotlines people could call around the clock if they had questions about their care. However, not all communication was well coordinated – we heard of one example where someone was contacted about their cancer diagnosis before they had received results from their diagnostic tests. This caused significant distress and highlighted the need to coordinate communications between system partners.

Care navigators, people who help guide patients through cancer investigations, diagnoses, treatment and ongoing care, also played a key role in ensuring holistic care was maintained during the pandemic. They were critical in meeting people’s social, psychological and physical needs as many ancillary services were less available during the pandemic period. We heard how up to 1,500 breast cancer patients with remote access were managed by care navigators in one system.

Initiatives focused on improving wellbeing, general health, exercise, rehabilitation, providing psychological support and social contact. Macmillan was also mentioned frequently by systems as being a source of additional information through the provision of webinars as well as one-to-one support. In Greater Manchester, the Prehab4Cancer programme, which offers exercise, nutrition and wellbeing support, was offered virtually and so remained accessible to patients.

People’s experience

People have been affected by the changes in cancer care. We heard about two patients who reflected on changes to the support they could previously access and how this has affected them:

- “My clinical care has continued as normal. But the support group has stopped and worse of all my counselling. She [counsellor] was provided by the group (charity). I went to her because I was depressed and had post-traumatic stress disorder due to the diagnosis, treatment etc. When the lockdown happened, this stopped. I was upset […] It was very hurtful.”

- “Ongoing support from the breast cancer charities has been online and difficult. Relatives were not involved except on the phone. In many ways this would appear not to make a difference, but I believe it's made a huge psychological impact. There is a subliminal quality to a consultation that cannot be obtained unless you are there. There is a huge element of support that is obtained from the shared narrative between others also on that terrifying journey. That shared narrative is lost and with it the feeling of pain and bewilderment increases. There was no option in the pandemic, but we need to get that narrative support back. Relatives need to share the journey to really be there. It's massive, really massive. I'm lucky, I can arrange private psychology support. Most can't do that, and I worry for them.”

We also heard about concerns around services’ visiting policies and how this impacted on families, particularly those that had suffered a bereavement.

“My wife was unable to come into the hospital when I was taken in at one point and I didn’t have a phone with me, so it was difficult to contact people at home. I had to be dropped off and picked up at the main hospital door for a biopsy and I felt alone.”

We heard that several providers were able to offer virtual sessions to support people. Sometimes this gave more time for people with clinicians than in face-to-face appointments. Despite this, we heard that sometimes it was hard to access certain wellbeing services and support groups, and we heard about some wellbeing-related therapies that were completely cancelled.

In Cambridge and Peterborough, cancer leads reflected that restrictive visiting policies did not help personalised care. We heard that families were more removed from decision-making and onsite support than under previous visiting arrangements.

In some saddening circumstances, we heard reports of relatives not being able to get in touch with their unwell family members before they died.

One of the key elements of cancer care is the provision of ongoing or palliative care and the decision-making process surrounding this. As part of this review, we reviewed 48 cancer patient records on the palliative register. We found that 54% of people had their cancer care plan reviewed in last 12 months, and worryingly only 35% of people had discussed ‘do not attempt cardiopulmonary resuscitation’ (DNACPR).

Even fewer people had had a discussion around their preferred place of death. Although we reviewed a small number of cases, it highlights the need for the system to recognise and consider the wider implications of the pandemic on long term community cancer care and perhaps take steps to address these issues. Issues with DNACPR were not uncommon during the pandemic as identified in our report ‘Protect, connect, respect – decisions about living and dying well during COVID-19’.

3. Keeping people safe

Key points

- Across the systems we reviewed, services described how the frequently changing COVID-19-related guidance during the pandemic posed an extra challenge in keeping people safe.

- Collaboration occurred between providers locally to make sure that they had definitive lists of the most vulnerable people.

- Health inequalities have been exacerbated by the pandemic – local systems have tried different ways to reach and protect people across their communities, but the initiatives have not always worked for everyone.

At the onset of the pandemic, systems responded quickly to establish accurate lists of their most vulnerable patients to disseminate shielding guidance. We have heard how vulnerable patients were identified using data from electronic prescribing and medicines administration systems, followed by patients having detailed discussions with their GPs about shielding or letters sent to the patient’s home.

In Leicester, Leicestershire and Rutland we heard how the local authority had taken further steps to provide more support to people who were shielding and implemented a community outreach hub. However, we also heard across systems how shielding guidance was sometimes applied inconsistently – this meant patients with the same health condition(s) were given different shielding information depending on where they lived.

When COVID-19 vaccinations became available, systems reported that they made efforts to ensure immunosuppressed patients were prioritised for vaccines. In Dorset and in South West London, NHS staff linked with GP practices to enable patients receiving or scheduled for cancer treatment, to have their COVID-19 vaccination urgently.

Some systems made sure that patients received their second dose of the COVID-19 vaccine before treatment and this was further extended to those caring for people with cancer.

We heard that to protect vulnerable patients further, the cancer alliance in Surrey Heartlands was instrumental in work with providers from outside their integrated care system (ICS) to help make sure cancer patients were offered a COVID-19 vaccination as a priority – this resulted in changes to national guidance. Other systems fast-tracked or reviewed whether COVID-19 vaccinations could be accelerated for cancer patients.

We heard how patients were fearful of COVID-19 and felt uncomfortable visiting hospitals and other clinical settings. There were reports of patients deferring their appointments altogether, which left providers across several systems trying to manage people’s anxieties around the virus. We have also heard about the psychological stress from COVID-19. One patient reported:

“[There has been a] lack of proper exercise and affected mental health, which means many of us have probably deteriorated physically and mentally over this 10 months of [the] pandemic, and that may have affected us as much as the general stress.”

We heard about a system awarding funding for psychology training for staff, to offer patients more support, and another system adapting cancer care specialist and nurse specialist roles to provide people support over the phone. Some systems and national organisations produced online videos to reassure people that services were safe to attend and to keep people informed. We also heard from one system that some GPs were reluctant to visit a residential home during the first wave of the pandemic. This meant paramedics were attending the service instead, creating an extra burden on the ambulance service at a time when they were already stretched due to COVID-19.

We have heard that systems introduced new infection, prevention and control (IPC) measures to protect patients and staff in hospitals and other clinical settings during the pandemic. One strategy involved the routine testing of patients and staff for COVID-19. From Surrey, we heard how anaesthetists and theatre staff worked in teams to ensure they did not treat both COVID-19 positive and COVID-19 negative patients; when they rotated, they were tested beforehand to ensure COVID-19 was not inadvertently transmitted.

“… every time I went, I was asked the same four questions about COVID, the reception asked everyone that I saw, there was very clear marking to note where to go, seating was distanced. Everyone wore masks and appropriate PPE, PPE changed appropriately, everything cleaned. Absolutely 100% safe. They were excellent.”

Rigorous cleaning protocols were also put in place, but these brought their own challenges. In one hospital, these protocols meant that fewer patients could have an operation during a theatre session – as a result, more sessions and staff were required to meet the service demand. We heard that hospital staff in one system found IPC guidance stressful because it kept changing, leading to inconsistencies in the way the guidance was interpreted and some patients losing trust.

As part of these measures, we heard about areas being identified as ‘green sites’ to help providers reduce the risk of COVID-19 transmission. ‘Green sites’ are hospitals or areas within hospitals that are declared COVID-19 free. We heard how the cancer hub in Greater Manchester had created a surgical standards document outlining the minimum standards for all green sites to ensure services were delivered safely and consistently in the area. Green sites in some systems were facilitated through mutual aid arrangements between system providers and independent health services.

In one of our reviews, we heard that the Christie and Rochdale Infirmary were identified as green hospital sites, and that this enabled the hospitals to increase their elective cancer surgery - and continue services, such as chemotherapy and radiotherapy across Greater Manchester.

The importance of service design was highlighted during some interviews. We heard how during the pandemic it became more apparent that service layout and design for some providers were more conducive to supporting effective IPC practices. Providers used side rooms to care for patients in isolation away from other patients and staff and introduced designated pathways to and from certain services to reduce the flow of people in and around specific areas. We heard that providers wanted to ensure that future service layout and design had effective IPC in mind.

Tackling inequalities

The pandemic presented systems with new challenges surrounding health inequalities. There was a rapid increase in the use of digital technology to provide cancer care and declines in cancer referral rates and numbers of patients attending appointments due to fears around COVID-19.

Also, COVID-19 presented a greater risk for people from Black and minority ethnic communities, older and disabled people and people living in deprived areas. It also exposed existing challenges including communication and language barrier and engaging people at risk of not accessing care. We also heard how, despite several systems starting or planning ways to address these issues in their areas, some providers were unaware of their system’s plans to tackle health inequalities.

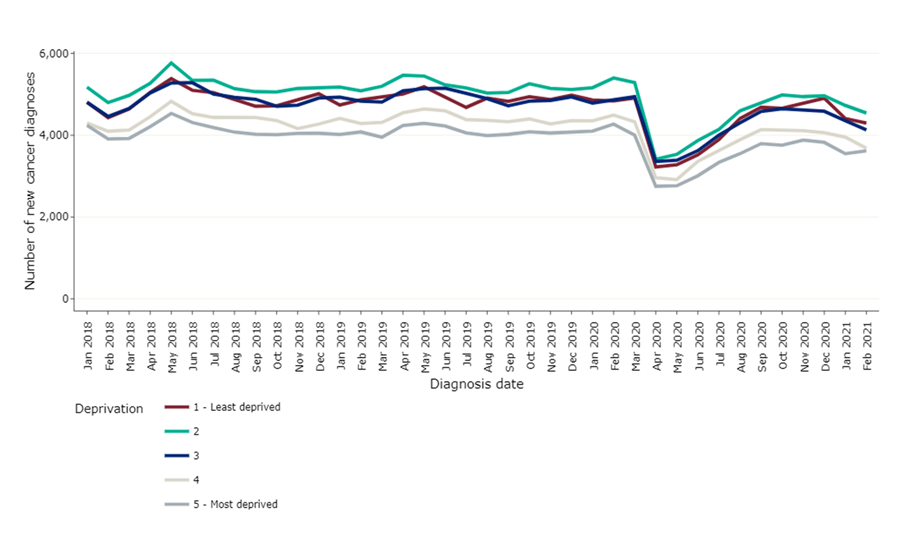

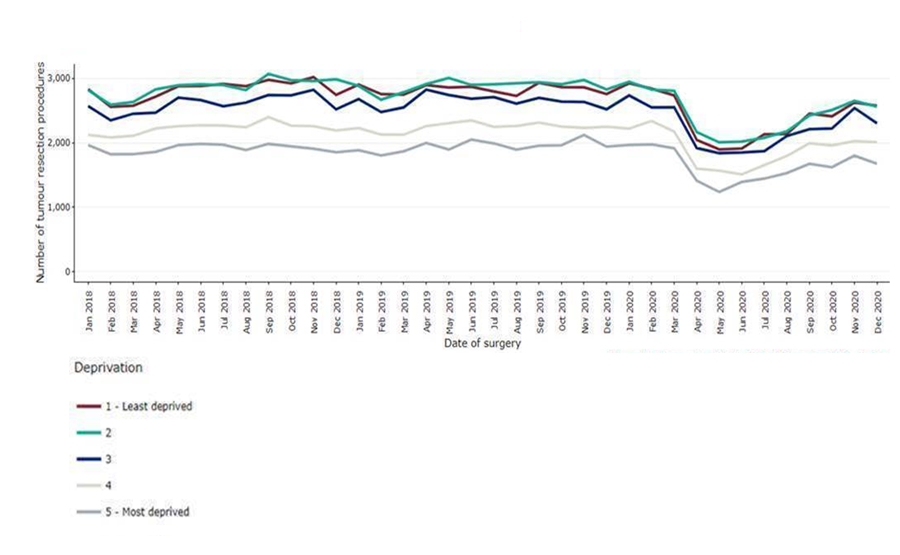

There has been a significant reduction in two week-wait referrals and new cancer diagnoses, and we heard that this may have affected some communities more than others. There is some evidence that more deprived communities have been more affected by the reduction in two-week waits and reduction in treatments (see figures 5 and 6).

This work has been produced by the National Disease Registration Service

This work has been produced by the National Disease Registration Service

Providers mitigated for some risks by engaging with their communities. We heard how they involved communities to promote awareness and use of cancer services during the pandemic. A community pharmacy representative told us how their involvement in early detection of signs/symptoms of cancer and symptoms management could relieve pressures on secondary care and improve access for patients.

Systems tailored communications for specific communities – providers targeted areas or groups of people to discuss cancer care and explain the benefits of receiving a COVID-19 vaccine. Some of the strategies used included translating information into different languages and creating online videos and social media campaigns.

A few systems targeted people at increased risk of not accessing care, such as traveller communities and people who are homeless to improve their access and understanding of cancer care. For example, in Cambridge and Peterborough, the GP cancer lead worked with North West Anglia Foundation Trust (NAWFT) to set up a working group to adapt the cancer pathway for traveller communities. The services held a focus group with approximately 30 to 40 traveller families to discuss aspects of care and barriers to registering with a GP. The primary care service was then awarded funding to identify specific GP surgeries where people from traveller communities could register.

The same system developed a policy to support the identification of vulnerable people as they entered the cancer referral system, to ensure they received the necessary support.

- We heard how systems responded to a reduction in cancer referral rates by identifying areas where cancer screening uptake was poor, and there were efforts to target cancer screening messages. We heard about local examples including: low attendance at breast screening clinics among people from Black and minority ethnic communities encouraged Community Links in South West London to coordinate a diverse group of facilitators to contact patients who were of the same ethnic background and encourage them to attend cancer screening appointments. We heard the initiative encouraged many patients to attend subsequent screening appointments.

- A decline in primary care attendance and referral for lung cancer diagnosis at the beginning of the pandemic encouraged system leaders in Surrey Heartlands to share targeted information using local media as additional support for people seeking advice for symptoms suggestive of cancer.

- The Cancer Alliance in Bath and North East Somerset, Swindon and Wiltshire displayed lung cancer awareness messages inside vaccination centres in areas with high deprivation and smoking rates as part of their targeted lung pathway campaign.

On a provider level, we heard how some conducted routine and follow-up calls to remind and encourage people to attend screening appointments. Additionally, we heard how providers collaborated to ensure information about cancer care was inclusive across different languages and that information about cancer pathways could be easily understood. Some providers used their multilingual workforce to create videos to inform people about delays to waiting times, communicate the importance of attending appointments and encourage people to get vaccinated.

In one review, we heard how the Leicester City Primary Care Network had started work with the university to produce social media videos in a variety of languages, voiced by people from those communities, to highlight the importance of attending screening appointments.

We also heard that written communication was made more accessible for people with a learning disability. This was done in Greater Manchester where Faecal Immunochemical Test (a test for bowel cancer) follow-up letters were changed to help people have a better understanding of the process.

Other inequalities exacerbated by the pandemic

The use of digital technology and social media was widespread during the pandemic and its implementation greatly accelerated (see Use of technology). However, some systems acknowledged that some people found this more challenging than others. For many reasons, such as limited or no access to the internet or digital technology, or a lack of privacy (people living in multi-generational households) some found it more challenging to access cancer care during the pandemic. Community pharmacy has supported local communities by ensuring a walk-in service remained in place during the pandemic with face-to-face support.

Some systems have been trying to mitigate the risk of people being negatively affected by the increased use of digital technology. In Dorset the NHS trust and local authority have been working together to increase internet coverage and provide people with equipment if they cannot afford it. In addition, a provider in Cambridge and Peterborough worked with their local authority to ensure people had access to transport if they were unable to access digital consultations. Another system reported building in equality impact assessments into the use of digital platforms but have acknowledged that it was too early to determine the impact of increased use of digital technology on health outcomes of cancer patients.

While some services have become more accessible to people due to increased technology and provision of care in patient’s home and local communities, we heard examples of the pandemic disrupting service provision for others, including the financial sustainability of hospices and people receiving end of life care.

We heard from Surrey Heartlands that some hospices had to temporarily close, citing a decline in donations and fundraising.

As part of our review we examined 48 patient records for people with cancer on the palliative care register. Of these, only 65% had anticipatory medicines (medicines kept at home to improve comfort at the end of life) prescribed if this was deemed appropriate and may highlight this challenge further.

We also heard how the pandemic had affected teenage girls. HPV vaccinations for protection against cervical cancer is usually administered in schools. In Surrey, as children were in school inconsistently, HPV vaccinations could not be given, and some girls were missed.

Lastly, one system told us that the new approach of using central cancer hubs was not always equitable. We heard how some patients did not have cars and would therefore struggle to travel long distances to reach centralised hubs. They reported that in the future, the structure would need to be more agile and ‘hubs’ may not be the optimal approach to take.

Plans to tackle health inequalities

The impact of the pandemic brought health inequalities to the forefront and some of the measures taken were reactive despite awareness and enthusiasm. Efforts to identify and tackle health inequalities among cancer patients were not well established across some systems, which may have stemmed from an absence of a system-wide strategy.

Consequently, some providers reported that they did not have a clear vision of how health inequalities among cancer patients were being addressed within their system.

During one review, it was noted that although there were governance structures in place, the lack of a cancer strategy prevented a clear vision of the aims and objectives of the system. In this review, it was evident there was a vision and work was being done, but there was some way to go for the system to understand population needs, inequalities and the challenges for the system.

One factor that may have influenced the lack of health inequality strategy within cancer services is the difficulty in recording people’s demographic data. Most systems reported that there were gaps in recording people’s demographic data, which may have affected how well providers could monitor people moving through cancer pathways and understand how health inequalities may have affected their experiences.

However, some systems have started to amend these problems by introducing processes to use available data to help inform their decision-making around health inequalities. In Bath and North East Somerset, Swindon and Wiltshire a coordinated approach was taken to review cancer waiting times and prioritisation to ensure that there was no disparity between patients from different geographical locations.

This involved sharing waiting list details within system meetings and development of a formal process for mutual aid if required. We also heard how plans have begun to be made around recording and using people’s demographic data for example, in Greater Manchester to help inform local planning and strategy around health inequalities in the future.

We also heard how some systems have started to develop more sophisticated programmes of work involving the collaboration of key stakeholders to start addressing the existing health inequalities. Some plans involved providers engaging with communities and raising awareness of cancer and encouraging screening uptake in people from Black, and minority ethnic backgrounds or poorer communities. Some examples include:

- Bath and North East Somerset, Swindon and Wiltshire are completing work to understand cancer waiting times and access, with consideration to factors related to protected characteristics and rural communities. They have begun tracking people from Black and minority ethnic backgrounds on cancer pathways against white patients. This is accompanied by commissioned work to review elective strategy to tackle health inequalities, focusing on protected characteristics and more widely across considerations such as mental health and rurality.

- The CCG's system wide Health Inequalities Framework in Leicester, Leicestershire and Rutland was developed in collaboration with key stakeholders within the system and partly focused on cancer screening uptake and cancer outcomes among minority ethnic groups and less affluent parts of the system. Meanwhile, the Cancer Board has started to develop a 10-year plan to have strategic oversight for health inequalities and the local authority is developing a three-year programme alongside housing, public health and clinical commissioning groups to address some of the wider health inequalities using ‘Better Care Funding’.

4. Governance and shared planning

Key points

- Established integrated care systems were able to adapt their governance structures in response to the pandemic so they could make quicker decisions and help deliver cancer services.

- There was recognition that adult social care providers were not always sufficiently involved in the local systems planning and strategies.

- Positive changes from the pandemic should be continued, such as the increase in community care, as well as the appropriate use of virtual consultations to help reduce waiting times and enable more patients to receive care in their own homes, community diagnostic centres, or community pharmacy.

All systems that we reviewed reported that cancer services were a key priority during the pandemic to ensure the continuation of national priorities including prevention, early detection and treatment. Several systems reported that providers were less protective of their own resources in order to support one another in maintaining service provision.

From Macmillan we heard that many hierarchies and bureaucracies were broken down between health and social care during the pandemic, leading to more integrated systems. However, some systems already had established integrated working approaches before the pandemic, and this enabled an easier transition to more widespread system collaboration during the pandemic.

Communication has been paramount in maintaining effective collaboration and systems have developed good ways of sharing information. In Dorset, dashboards to share data had been developed to disseminate information with system partners quickly. We also heard about effective governance structures within systems to augment this whilst also facilitating partnership working.

We were told local medicines optimisation leadership cells supported cancer services and maintained close working relationships with cancer alliances to ensure knowledge and guidance was shared with smaller acute trusts. This provided assurance across the system for the availability of medicines and staff, and a more collaborative way of working especially for service redesign.

Some systems reported how they had adapted and reviewed their governance structures in response to the pandemic, in order to deliver cancer services. For example, we heard that the South West London ICS had a good structure in place, but it adapted its governance to enable rapid decision-making and the equitable provision of services.

Another way that we heard systems improved partnership working was by using multidisciplinary meetings and regular system-wide calls. For example, in Greater Manchester, virtual multidisciplinary team (MDT) meetings regarding colorectal cancer increased clinical oncology input. Other systems reported the ability of wider system meetings to also facilitate monitoring of staffing levels, review pathways to balance system pressures, and share learning.

We heard from systems that were confident that their leadership had enabled successful collaboration during the pandemic. Effective leadership and a clear direction from cancer alliances often facilitated the delivery of cancer services across the system. We heard how strong and inclusive leadership from the cancer alliances helped identify and address risks, facilitate the cascade of information regarding changes to pathways, and enable decisions to be actioned through medicines leadership calls.

We also heard reports that the pandemic had formalised and strengthened relationships within systems. One of the most frequently reported developments throughout the pandemic was the development of system ‘hubs’, though some of these may have existed before the pandemic.

Several systems reported the use of community diagnostic hubs and palliative care hubs. One system highlighted the use of an integrated hub, which included acute care as well as hospices and adult social care to support a multidisciplinary approach to cancer services. There were innovative approaches in another system, such as system partners working together to support adult social care providers with training around mental health and mental health needs of people with cancer.

Systems partners were able to support one another. In Leicester, Leicestershire and Rutland, the local hospice developed an integrated service in the community by working with the community trust to provide a 24/7 rapid response. We heard this helped to provide support to the community trust and that people had better access to care. Overall, we heard there was improved access to additional resources (particularly medicines and equipment), and better access to staff and premises, which subsequently improved access to services and served to better join-up pathways.

This collaborative approach was paramount in the delivery of community and palliative services. This involved some systems using community services, so patients did not have to attend hospital and could receive care closer to home. These services included diagnostic hubs, a breast pain clinic, community pharmacies delivering specialist secondary care medicine and outreach support in the community.

We heard from two systems that acute palliative care teams worked closely with hospices and GPs to provide seamless end of life care. In South West London, end of life care nurses supported linked care homes. Although there had been historical problems with supply of medicines used for end of life care, we heard across systems that there was good coordination ensuring availability was maintained. One system explained that having nurse prescribers in the hospice meant that an alternative medicine could be prescribed quickly if there was a supply problem.

Provision of training was another important factor in delivering community care. We heard how some systems supported staff training about end of life care, which also involved learning to use syringe drivers (an important piece of equipment in the administration of end of life medicines). In Greater Manchester, training opportunities were also provided regarding DNACPR decisions. This was delivered virtually to improve distribution to key stakeholders.

We heard that the independent sector also worked well with some local systems as part of national initiative. In Bath and North East Somerset, Swindon and Wiltshire, private providers were able to provide imaging services such as ultrasound, CT and MRI scans to free up the NHS trust to perform other work.

Hospital pharmacies worked closely with the private sector to deliver care. This included greater use of homecare services to deliver and administer medicines, as well as special private units to produce chemotherapy and free-up capacity in NHS services. This worked well in systems where regular status updates were held, ensuring risks could be mitigated.

We were told by several systems that increased outsourcing and use of external companies was likely to continue beyond the pandemic. We heard that close collaboration between central NHS departments and the independent sector was needed to provide quality assurance and ensure stability of these supply chains.

Systems shared challenges for the planning and delivery of cancer services across systems. There were also concerns that some of the new relationships developed during the pandemic might not be sustained.

We heard that another challenge was the lack of integration of some key providers – some system partners did not feel a part of the wider system. Although we have heard examples of good integration of adult social care with healthcare services, this was not apparent in all systems we spoke to.

Planning and strategy considerations for adult social care within cancer services was one of the prevalent challenges – one system recognised the need for adult social care providers to have “a clearer and stronger voice in the system”. Within the wider system, there were also reports that some providers also did not feel well integrated in delivering cancer services.

System recovery

All systems had a plan for recovery post-pandemic, mainly aimed at addressing the backlogs in cancer care due to the impact of COVID-19 on health services. This included plans at both system and local level and was supported by NHS England and NHS Improvement as well as local cancer alliances.

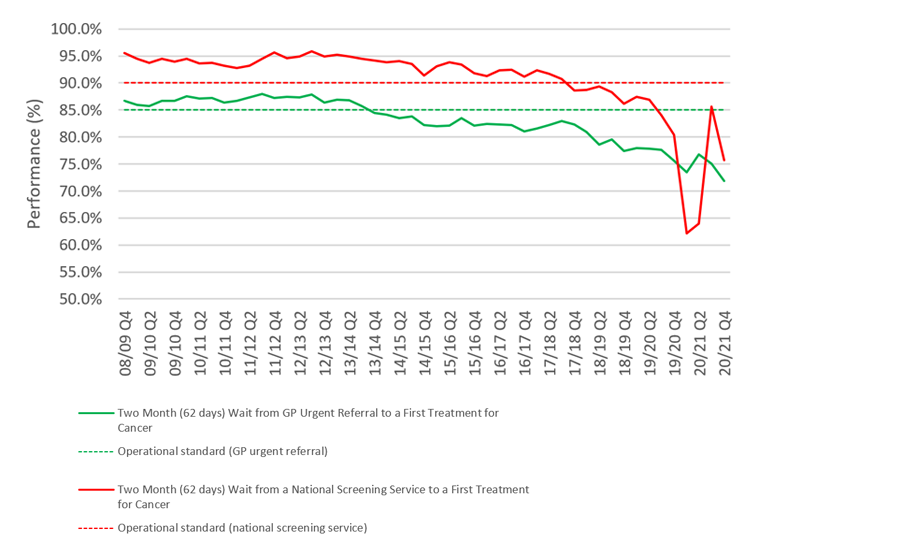

In Greater Manchester, recovery planning continued across three bowel screening programmes, working in accordance with national guidelines and providing colonoscopies to patients with a positive faecal immunochemical testing result. Figure 7 demonstrates the number of patients starting treatment following referral from their GPs or national screening services dropped sharply.

Source: NHS England, cancer waiting times data

In planning for system recovery, many systems reported weekly meetings to review, and assure recovery plans. Networks grew and this enabled better sharing of learning and best practice.

We heard that providers also noted that integrated communication systems, such as patient tracking lists, would enable smoother connections and inevitably more joined-up care. In one system, the system-wide recovery was managed by the acute trust and a cancer quality and performance committee.

In Greater Manchester, we also heard how the cancer alliance played a key role in service delivery and service recovery. Similarly, in Surrey, we heard about the role of the local cancer alliance and its funding to increase booking teams and provide access to endoscopy at the weekend, which contributed significantly to the reduction of their backlog. This was further enhanced by the creation of a recovery dashboard to allow identification of barriers to recover and early intervention to overcome these. There were efforts (figure 8) during summer 2020 to clear some of the backlog nationally.

Source: NHS England, cancer waiting times data

At the time of our review, it seemed that most systems in our review had recovery plans in motion, especially for reducing screening backlogs. We heard how two systems had successfully made progress with waiting time targets, and another considered their recovery plan to almost be complete due to the return of redeployed workforce and outsourced services.

There was debate about whether this may have been achievable because of low referral numbers, possibly due to people not presenting or being referred. Despite national reports of backlogs, we also heard how some systems had maintained pre-pandemic service levels. One system reported that their cancer services had not been greatly affected by the pandemic. Another system reported that they had never failed to meet the 31-day target, however they did not have high rates of COVID-19 in the system in comparison to the rest of the country.

Sustaining positive change and future challenges

We talked with systems about their desire to sustain the positive changes that were made during the pandemic. Increased funding and collaboration were considered to have contributed to some successes within systems.

Systems also expressed their desire for the increase in community care to be sustained in the future. This included the use of virtual consultations to reduce waiting times and enable more patients to receive care in their own homes, community diagnostic centres, and community pharmacy.

The increased prevalence of advanced stage on diagnosis patients was of concern to system recovery plans.

However, systems also reported additional causal factors including a reduction in routine activity. This meant that screening was delayed and cancers which would have been found incidentally on routine checks could have been missed. This was particularly problematic for lung cancers as the symptoms are similar to the COVID-19 infection symptoms.

One system reported that future working, resourcing and staff skill mix may have to consider the possibility of treating sicker and more complex patients.

Resourcing for additional screening, diagnostic and surgical capacity to address the backlog was also discussed with several systems. There was recognition of the need for dedicated endoscopy capacity in order to return to pre-pandemic levels of activity and cope with the increased demand.

Other examples include the use of rapid diagnostic centres and mobile units, returning to ‘straight-to-test’ pathways where GPs can refer patients directly for a diagnostic test, as well as utilising allied health professionals to undertake additional screening appointments (for example, cervical smear tests). Despite these potential solutions, there are still many unknowns and barriers, such as stretched resources and the need to comply to strict IPC measures that may delay system recovery.

5. Staff skills

Key points

- There are concerns about the long-term impact of the pandemic on staff – with pressure on recovery, systems point to a depleted workforce and ‘staff burnout’ as a real problem.

- Systems have used mutual aid and upskilling initiatives to make sure cancer services were maintained where possible, but in some places the redeployment of staff adversely affected cancer services.

- Systems used risk analysis to understand which staff may be more vulnerable to COVID-19 – emotional and psychological support was also available.

We have heard how staff in health and social care systems have worked differently during the pandemic and there have been some creative solutions to help people who need care. Systems were actively monitoring staffing levels, absences, skills mix, and availability of people to work in different areas. This was to ensure that there were enough staff, with the right skills, to meet the demand of cancer services.

University Hospital Dorset, for example, used a dashboard to monitor staff sickness levels, and weekly meetings to identify and address any emerging staffing issues. It appears that coordination and communication were beneficial in this regard, and the system would like to maintain this way of working going forward.

Systems told us that this approach may also be useful in actively planning and managing staffing levels and skills for recovery. There were concerns about future staffing due to the possibility of patients with more complex problems, as well as workforce burnout and staff retiring.

We heard the recovery of endoscopy services will depend on staffing levels, and systems have advised that sustainable future planning will need to be carefully considered.

The impact of staff shortages and redeployment was felt in cancer services. We heard from systems that this will continue to become a challenge in the system recovery.

We heard how some cancer operations were postponed as consultants were redeployed to intensive care units, and how cancer nurse specialists were overstretched. We were also told of the demand for an increase in pharmacist prescribers for cancer care, while some hospital pharmacies could enable this, others were worried about the impact on core services. With capacities being exceeded, there have been concerns around staff health and wellbeing. For example, we heard about staff working additional hours to catch up on screening backlogs, raising concerns around burnout.

In response to staff shortages we heard from several systems that creative solutions were found, including upskilling and training of staff. In some cases, this enabled staff to work in different, new roles.

In Leicester, Leicestershire and Rutland, a local hospice redeployed allied health professionals to acute and community trusts, where they were able to learn new skills. The hospice is looking to use these newly acquired skills going forward to enhance people’s experience. In Greater Manchester, nurses with critical care skills were given refresher training and were placed on a shadow rota to be redeployed if needed.

Changes were also made to ensure staff were used effectively even if they were shielding. Many systems used digital technology to support home working, which was able to improve productivity and flexibility (see Use of technology).

The use of mutual aid in maintaining staffing levels was apparent in our conversations with systems. It sometimes meant that staff did not have to be redeployed and instead, offered providers flexibility to get extra support when needed.

For instance, collaboration among cancer alliances in London to introduce a passport for pharmacists allowed staff to move between organisation without the need for reaccreditation or further training. An electronic version of this passport launched in early 2020 and was ready for use during the pandemic. Other solutions involved using bank staff to fill some of the staffing gaps and using volunteers to support services.

Staff safety and wellbeing

The COVID-19 pandemic put healthcare workers at greater risk due to the increased likelihood of exposure to the virus in clinical settings. We heard that working during the pandemic may have led to staff being more stressed, exhausted and under emotional strain.

Providers across systems told us about measures they took to protect staff from COVID-19 infection. This included protection of staff who worked face-to-face with people, but also enabling vulnerable staff to minimise contact. In some cases, measures that were predominantly meant to protect people accessing service, also had the added advantage of protecting staff.

Risk assessments and PPE distribution happened in all the systems in this review. However, despite mutual aid in the provision of PPE, some providers experienced shortages at the beginning of the pandemic.

Testing and vaccination for COVID-19 were other measures that were reported. Most systems told us that staff were regularly tested and prioritised for vaccination. In South West London, staff were also actively educated about the vaccine to improve uptake.

As well as attending to physical health needs, all systems reported there was a strong emphasis on psychological and emotional support. An acute trust in Bath and North East Somerset, Swindon and Wiltshire developed virtual counselling sessions for cancer services staff. In Shropshire, Telford and Wrekin, an acute trust provided outdoor areas and additional space in multi-faith prayer rooms to allow for social distancing.

In one trust, free parking for staff was also offered so staff could avoid using public transport. These types of measures were placed to improve and address any mental health impacts that staff may have encountered due to working through the pandemic. However, it was stressed that staff mental wellbeing may be a challenge in the future and active monitoring may be required.

During the pandemic we also heard how people from Black and minority ethnic backgrounds were more likely to be severely affected by COVID-19 and so we asked systems about measures they took to protect these staff groups. We heard that in some systems staff from Black and minority ethnic backgrounds had opportunities to come together to raise and discuss questions during the pandemic. This was through virtual meetings, meet and greet events or proactive conversations.

During one review, we heard how at the Christie hospital in Manchester, there were specific opportunities for medical staff to discuss and ask questions about cancer care and the pandemic - concerns went back to the clinical advisory group. These opportunities were streamed and recorded for staff who were shielding or working from home. Providers in all systems performed risk assessments for all staff to establish their level of risk from COVID-19 with staff ethnicity being one of the risk factors. This was then used to determine how best staff members could be supported to work safely, for example, by working from home or redeployed to work in COVID-19 free areas. Staff were also supported to return to normal places of work safely when it was appropriate to do so.

On our review in Greater Manchester, there was a coordinated approach across the system using a single unified risk assessment for staff from Black and minority ethnic communities. We heard that this was developed with engagement from local Black and minority ethnic forums across the system. The NHS Black and minority ethnic community had a regional presence on the cancer board. We heard that where staff were high risk, they were redeployed to work at the Christie or Rochdale Infirmary, which were identified green sites, or they worked from home.

Impact of redeployment on services

Despite cancer services being prioritised by systems during the pandemic we received a mixed picture in terms of the extent, and impact of, staff redeployment on the provision of cancer services.

Some systems reported facing significant challenges around workforce capacity. Most commonly, we were told of the redeployment of anaesthetists and theatre nurses, cancer/clinical nurse specialists, medical and surgical consultants, including those within endoscopy wards. Staff were primarily redeployed to support intensive care units and some radiologists were redeployed to focus on COVID-19 imaging.

As a result of this we heard that there were significant effects on screening services and surgery. This included a reduction in theatre capacity and the cancellation of surgery due to the lack of anaesthetic support.

We also heard that early in the pandemic hospice staff were redeployed to critical care and palliative care staff deployed to acute and community trusts. The limited availability of specialist cancer nurses initially affected the provision of personalised care in one system. However, in other systems, redeployment was minimised as cancer services were ring-fenced. We also heard how redeployment was ceased after the first wave of the pandemic in response to service and care needs in some systems. In Greater Manchester, palliative care staff had initially been redeployed to support intensive care, but this was reversed when end of life work volumes increased.

The use of mutual aid and collaboration was also helpful in reducing the impact of redeployment. Collaboration within and across providers was able to mitigate the impact of staffing challenges and changing capacity needs. For instance, one system told us how they used outpatient healthcare assistants to support oncology teams by adapting their roles.

Additional funding was also of use in ensuring that cancer services had access to enough staff with the right skills. Extra financial support to introduce cancer site navigator roles in Cambridge and Peterborough meant that patients were able to maintain contact with cancer nurse specialists and receive advice and personalised care. This resulted in continuation or minimal disruption of services and ensuring continuity of care.

In one review, an acute trust had allocated new resources to help ensure that patients continued to receive personalised care and had holistic needs assessments completed. We heard that the trust had created navigator roles for larger cancer sites such as breast, skin, lung, haematology and urology. These people managed phone lines and signposted patients appropriately and completed holistic assessments for their patients.

6. Use of technology

Key points

- Digital solutions and technology have helped many people with access to the cancer services they needed during the pandemic.

- Local systems focused on rapid improvements to online solutions – there were some innovative approaches with good outcomes for providers and patients, but online consultations are not ideal for some consultations and attempted diagnoses.

- Not everyone can access care via new technology, and because of the accelerated developments there are some confidentiality issues to overcome.

The pandemic has been a catalyst for some improvements in the use of digital solutions and technologies for both remote working and the delivery of care. These have been valuable in sustaining access to cancer services and providing safe care for people who use services during the pandemic.

An overarching aim across the various systems was ensuring access for patients. This included access to health care services but also access to information, records and staff with specific expertise.

We heard that one of the most prominent strategies was setting up digital solutions to support remote working for healthcare professionals. Although the solutions were not necessarily novel, the pandemic promoted the improvement in and use of digital solutions and technology.

Remote interactions between people and healthcare staff was beneficial across all systems and services. The ability to have a consultation or treatment at home helped reduce the chance of infection for potentially vulnerable people and control the spread of the virus. We heard about improvements to existing video, telephone and online technologies across all systems. In addition, some systems reported that they adapted their current operating models and processes around patient appointments to better support remote consultation, assessment and treatment of patients.

Remote working was broadly defined into two categories within primary care. Firstly, patients’ access to GPs and the GP’s remote access to patient records. Most systems reported investing in new solutions to support this model of working.

Most systems focused on improving technology in order to be able to offer online consultations, but we also heard about some more innovative examples. In Shropshire, Telford and Wrekin, a platform called Shropdoc was developed to help people access GP services when their local GPs were closed or unavailable.

In Whitely Village in Surrey, we heard about the Whzan Blue Box project. This is a case containing key instruments needed in self measuring vital signs, recording photographs, and calculating a National Early Warning Score (NEWS2). The local GP reported seeing positive results and GPs were better able to communicate and more rapidly assess and review. These benefits were not limited to cancer patients but all those using the service.

Another example we heard about was focused on teledermatology, which used digital solutions to allow patients to send photographs of any skin or mouth lesions to their GPs. These processes were used by both community teams and GPs to liaise quickly with skin cancer specialists, ensuring timely referrals. However, some clinicians reported that they had difficulties in diagnosing from photographs with poor photo quality, which poses its own challenge.

We also heard examples of remote working in acute settings. In Bath and North East Somerset, Swindon and Wiltshire, providers used online apps to set up virtual clinic reviews as well as virtual rehabilitation. In adult social care, we heard from Surrey how digital iPads were used to support residents to connect with their GPs. However, digital solutions directly relating to adult social care were not prominent and were mostly linked to innovations in other sectors.

We heard many examples of how digital solutions were used to support pharmacy teams. We heard how electronic systems were utilised for medicine procurement usage reports and efficient implementation of the new NICE guidance (NG161). Some ICSs or large areas within an ICS had fully integrated systems making transfer of patient records and access easier. For example, in one system care records were available to all healthcare providers across one of the systems making recording of administration in the patients’ home seamless. Looking to the future, one trust is collaborating with a pharmaceutical company to develop an app for use by cancer patients and community pharmacists, joining up primary and secondary care for patient more efficiently.

It is clear from the findings that remote access to care had many benefits for system providers and service users during the pandemic. However, we also identified several key challenges and limitations of this way of working. These can be broadly grouped as challenges with remote diagnosis, and challenges with telecommunications.

Across systems, ensuring patient safety was a challenge in remote working. Different systems reported the inability to assess safeguarding concerns and ensuring patient welfare through video and telephone supported appointments. Furthermore, one system reported on the difficulties of making a full clinical assessment virtually, and we also heard that some patients were referred inappropriately to cancer pathways.

This was one person’s experience during this period:

“I have had virtual consultations as well as in-person consultations regarding chemotherapy and further treatment. It's not so easy to discuss treatment on the phone with doctors one has never met, but I recognise why it has to be that way at the moment. It's difficult not being able to demonstrate where a pain is. I don't find it as satisfactory. […] In a way, telephone consultations avoid long waits in the hospital, but inevitably, one feels more alone and less supported, although I know everyone is doing their best.”

A key theme across systems that emerged when looking at challenges with telecommunications was the inequalities in access to digital technologies – this included digital poverty, digital exclusion, disabilities, and language barriers.

We heard that several systems identified that digital exclusion was widening health inequalities and would need to be an area of future focus in the development health and social care pathways. Some systems were aware of this and we heard some examples of how they addressed the challenge.

For example, administrative teams in Surrey checked to see if patients were able to have video or telephone appointments. This ensured that patients with learning disabilities or who did not have English as a first language were not booked into virtual clinics.

Breaking bad news was a key area of difficulty. We heard about several strategies used by the systems to tackle this sensitive issue and there were mixed experiences from providers and patients. In one system we heard how staff struggled with virtual calls for breaking bad news as they felt unable to provide holistic and physical support for patients. This was one person’s experience during this period:

“I found telephone consultations easy and informative – I think mainly because I have been seeing the consultant for some time and have a good rapport with him. Telephone appointments would not have been easy when first diagnosed and I have sympathy for people in this situation.”

Conversely, in several systems it was reported that some patients preferred receiving bad news at home where they had better support, family members were able to be with them and did not need to travel.

Virtual management of care

The virtual management of care was a theme we identified across the various systems. One particularly effective adaptation by multiple systems during the pandemic was the transition to virtual multidisciplinary teams (MDTs) using video-conferencing software such as Microsoft Teams.

In some systems we heard how virtual meetings improved attendance and provided new opportunities for teaching and education. The Dorset Cancer Partnership Programme reported that they were able to effectively manage their breast cancer backlog using these virtual MDTs. In another trust, virtual MDTs were utilised as a teaching resource for medical students.

Another component of virtual management of care were digital solutions that enabled the planning and tracking of patients and their information. The efficacy of digitalising and tracking patient information and tracking was demonstrated by the Greater Manchester Tableau System. This system enabled providers to manage cancer services with daily situational reports, which allowed decisions to be made by primary, secondary and community services efficiently.

A simple digital solution reported in south west London was the use of a messaging service where a group was set up by cancer clinical leads for internal communication. This facilitated a quicker transfer of information across different groups of colleagues.

As with other sectors outside of health and social care, we heard about some staff transitioning to work from home across all systems. Enabling home working through digital solutions ensured that system stakeholders would still have access to their staff and that their vulnerable staff could be protected.

Providers across the multiple systems provided their shielding staff with laptops and software which enabled them to continue to work despite the limitations of the pandemic. We also heard how radiologists in many systems were given technology to allow them to review and report imaging results from home.

Digital governance

As the use of digital systems to support remote care and its management developed and increased, there was a recognition by systems that good digital and technology governance was necessary. We saw that governance structures around digital solutions focused on two main categories: information sharing and confidentiality; and operating procedures/protocols.

An important consideration when looking at the governance of information sharing technology was ensuring that patient information was kept secure and confidential. Several systems reported developing approaches to ensure data was protected and one system reported that they had not had any adverse outcomes or confidentiality breaches as a result of digital technology during the pandemic.

All the systems have taken steps to develop operating procedures around the use of digital solutions and technology. Apart from information governance, these procedures focus on the efficacy of the technology and guidance around using the technology for its designated function. Examples of this included developing risk assessments on the potential impact of using IT equipment, developing standard operating procedures for holding virtual clinics and developing guidance to tracking and evaluating patient pathways.