Contents

Defining an ethnic minority-led GP practice

- Do ethnic minority-led practices have poorer ratings?

- Are ethnic minority-led practices more likely to be inspected?

- Do ethnic minority-led practices have a differential experience of the inspection process and outcomes?

- Factors internal to ethnic minority-led practices

- Factors external to ethnic minority-led practices

- Internal CQC factors

- Action to ensure equity of treatment for practices and to benefit patients

- Factors outside of CQC’s role where we could use our influence

Conclusion: Learning from what we found

- Appendix A: Statistical model for ratings

- Appendix B: Terms of reference for the sub-group of the Primary Care Quality Board

- Contributors

Summary

The Care Quality Commission (CQC) is committed to being a fair regulator. We consider equality for the organisations that we regulate, for people using health and adult social care services, and for our own workforce. We embed assessments of organisational and health inequalities across all aspects of our regulatory activity.

Providers led by GPs of an ethnic minority background have raised with us concerns that they do not receive the same regulatory outcomes from CQC as providers led by GPs of a non-ethnic minority background.

To investigate and respond to these concerns, we started a programme of work in February 2021. The focus of this has been on how our own regulatory approach affects ethnic minority-led GP practices and how we can improve our methods to address any inequalities we identify.

Our review used both quantitative and qualitative methods. These comprised reviews of our data and processes, an online community of 36 ethnic minority GPs, a survey of 771 GP practices, a survey of 57 CQC inspectors and focus groups with CQC inspection teams (attended by eight inspectors, four inspection managers and four GP specialist advisors). We engaged with key stakeholders, including subject matter experts, on our processes and findings.

The aim of our review was to understand the experiences of ethnic minority-led GP practices, rather than to reflect the experiences of all GP practices. It is important to note that because of the methods we used in this research, the results are reflective of the people who participated in our online community or responded to our surveys. Only ethnic minority GPs were invited to take part in the online community and so the views expressed in that forum may apply equally to non-ethnic minority-led GP practices. The aim of the online research community was to understand lived experiences of ethnic minority GPs, rather than to reflect and compare GPs’ experiences.

Regulatory outcomes and experiences of ethnic minority-led GP practices and the factors associated with them

Due to limitations in the data available to us from all partners in the system, we were unable to fully explore the nature of the relationship, or existence of any causal link, between ethnic minority-led GP practices and regulatory outcomes such as ratings and frequency of inspection.

Ethnic minority GPs in our research reported poor experiences of the inspection process and its outcomes. In our online research community of ethnic minority GPs, there was a feeling that their inspection outcomes could be “harsh” and “unfair”. They felt that CQC does not understand or appreciate the unique challenges that ethnic minority-led practices face.

In our survey of GP practices, ethnic minority-led practices were more likely to report that GPs in their practice experienced adverse impacts on their physical and mental health, a negative impact on their personal and/or family life, and had seen an increase in staff sickness as a result of the inspection process.

However, in this survey, ethnic minority-led practices were more likely to report that the quality of care improved following a CQC inspection.

External system factors

Most ethnic minority-led practices in our GP practice survey served populations with a high proportion of socio-economic deprivation. Both GPs and CQC colleagues identified socio-economic deprivation as a challenging factor, as it can affect the practices’ ability to achieve national targets that we use in assessments of quality, such as the uptake of immunisations or screening among patients. Some inspectors and specialist advisors felt our approach did not recognise enough the surrounding context of practices, and that some practices are disadvantaged for not achieving similar outcomes to those with very different contexts and patient communities.

The online community of ethnic minority GPs identified that deprivation also presents other challenges, such as increased workloads, as patients with poorer health typically need more care. These practices also experience difficulties with recruitment and funding. This makes it harder for practice staff to cope with patient demand, which again can have a potential impact on CQC regulatory outcomes.

Our online community also highlighted a perception of a lack of leadership support for ethnic minority-led practices from external bodies. In addition, some ethnic minority GPs reported experiencing racism from patients, especially when patient expectations could not be met. They also felt patients were more likely to raise a complaint about an ethnic minority GP than a White British GP.

Internal practice factors

Our survey of GP practices showed that certain types of practices are more commonly associated with being ethnic minority-led – for example, single-handed or individually led practices. We heard from our online community and in focus groups and interviews with inspection colleagues that it can be harder for smaller practices to spare the time needed for an inspection. In the focus groups and in the online community, we also heard that these practices experience professional isolation.

Responses from CQC colleagues also highlighted factors relating to practice management or leadership, including less familiarity with CQC regulation or poorer IT skills, reducing the ability to provide evidence at inspections. This may reflect a need for CQC to be more considerate of these differences to better support practices.

CQC factors

GPs in our online community felt that CQC’s need for objectivity potentially had a negative impact on ethnic minority-led practices and could lead to unfair outcomes, because methods are not able to be tailored to reflect providers’ circumstances.

There is a perception that the evidence used in inspections is a disadvantage to both ethnic minority-led practices and practices serving socio-economically deprived patient populations as the differing views of patients, such as a reluctance to receive vaccinations, affected practices’ performance when compared against national targets. Similarly, inspection colleagues and specialist advisors felt that website reviews and online feedback forms could disadvantage practices serving communities with lower levels of English proficiency.

CQC colleagues emphasised that their key priority was to ensure that care was safe and accessible, regardless of the challenging circumstances that practices might face. However, both CQC inspection teams and GPs raised concerns that CQC did not always take into account the innovations that practices had developed to respond to local needs.

Inspection colleagues and GPs thought that CQC’s terminology can impede ethnic minority-led GP practices from meeting data requests and regulatory requirements. Ethnic minority GPs in our online community highlighted a need for clear, transparent and accessible guidance as the lack of clarity may affect inspection outcomes.

Processes to challenge regulatory outcomes and ratings were also noted to have an impact on ethnic minority-led GPs, with some ethnic minority GPs in the online community perceiving a possible risk of victimisation, poorer ratings or re-inspection if they choose to raise complaints.

Ethnic minority GPs in the online community also raised the composition and skillset of inspection teams as an issue, feeling that inspection teams needed greater cultural competence, and an understanding of local areas and populations.

Improvements that could help promote equity in regulatory outcomes

Improvements for CQC

Both GPs and inspectors who responded to our surveys felt there could be more in CQC’s methods to reflect the specific context within which GP practices operate. They said that inspection teams should gather a wider range of evidence about how a GP practice meets the needs of its populations, including how the practice is reducing health inequalities. In the focus groups and interviews with CQC colleagues, we heard that this would help to recognise more responsive care and good leadership where a GP practice is operating in more challenging circumstances. It was also felt that inspection reports could reflect that lower ratings may be because of additional external pressures, rather than poor clinical work or a lack of concern by the practice for the wellbeing of its patients.

Ethnic minority GPs in our online community wanted to see a more supportive approach from CQC, better communication from inspectors and greater transparency about expectations, processes and decision-making.

By encouraging practices to engage more with our guidance and support, we can help them understand regulatory requirements and expectations. Practices felt a more collaborative approach would support providers and patients alike, as providers could discuss concerns without fear of repercussions, helping them work with CQC to improve.

Improvements for the wider system

A consistent theme from ethnic minority GPs was about the need for more support from the wider system. There was agreement that support from clinical commissioning groups (CCGs) can help a provider to improve, but in the GP provider survey, ethnic minority-led GP practices reported lower levels of good support from CCGs. In the online community, other partners in the system, such as the British Medical Association, General Medical Council and NHS England and Improvement, were also highlighted as having a role.

Inspection teams generally considered that the role of supporting providers sat with CCGs as opposed to CQC. However, some inspectors had experience of where CCGs had not acted to support GP practices as the CCGs thought it was CQC’s role. This suggests a lack of clarity about roles and responsibilities around supporting GP providers. It was suggested that CQC and CCGs needed to improve their working relationship and increase dialogue about the support practices need. It was felt that improving this relationship should not be the responsibility of individual inspectors.

What we will do

This programme of work was designed to look at our own systems and processes and how these affect inspection outcomes for ethnic minority-led GP practices. The findings show that there is work for us to do to ensure we achieve our strategic and equality objectives and deliver our core purpose to ensure we encourage practices that need support to improve.

The work has identified an inter-relationship between factors that can lead to poorer regulatory outcomes. Internal or practice factors often have a disproportionate impact on practices where many ethnic minority GPs operate. Ethnic minority-led GP practices are often operating single-handedly, which results in challenges in support, resourcing and capacity. These additional burdens affect the ability of a practice to show evidence that it is meeting regulatory requirements.

Importantly, there are also wider, contextual factors that affect ethnic minority-led GP practices – in particular the efforts required to respond to the health inequalities of patients in areas of deprivation. Practices in areas of deprivation struggle with lower funding and systems of support. This work has demonstrated the need for better system-wide engagement in addressing these factors and we hope to further this conversation through the findings from this report.

We will take the following actions to respond to the findings from this review:

- Continue our work through the Regulators' Pioneer Fund to support us to identify innovation in areas of deprivation and share good practice as part of our routine regulatory processes, assessments and engagement.

- Develop our approach to our new duty to review and assess integrated care systems, including a need to reduce inequalities for people who use services. In doing this, we want to address where local systems need to provide more support to ensure that primary care meets the needs of everyone in their population.

- Continue to work with our system partners in the sub-group of the Primary Care Quality Board to identify and progress shared priorities in ensuring equality for ethnic minority-led GP practices and the populations they serve. This includes:

- Reviewing what can be done within the wider system to ensure that single-handed practices are not unduly disadvantaged by the circumstances in which they work.

- Reviewing whether the current arrangements for supporting GP practices are effective for those in areas of deprivation that are experiencing disproportionate pressures, such as professional isolation and lack of funding.

- Reviewing and improving ways to capture feedback from diverse ethnic groups about the care they receive.

- While continuing to expect good quality of care for everyone and without compromising on expected standards of care, we will strengthen how we consider the context in which a GP practice works. This can include:

- Gathering a wider range of evidence about the efforts that GP practices are making to respond to the needs and health inequalities of their practice populations, as well as the outcomes of those efforts, and reviewing how we use this evidence.

- Ensuring that we reflect factors that could disproportionately (although not exclusively) disadvantage ethnic minority-led GP practices in our decision-making processes.

- Reviewing our quality control and assurance processes to consider whether we can do more to remove the risk of any potential bias.

- We will clearly explain our inspection and assessment processes and expectations of all providers so they are easy to understand. To do this:

- We will support all GP practices to understand how to give feedback, challenge our reports and ratings, and raise complaints. This will include reviewing our guidance (including factual accuracy and ratings review processes) to ensure it is clear and accessible to all providers and to inspection teams that support GP practices.

- Inspection teams will continue to build ongoing relationships with GP practices to help them understand our regulatory approach and requirements.

- Carry on implementing our new strategy, so that we work more closely with providers to better understand them and the needs of their populations, and to encourage more open and regular communication.

- Progress our Diversity and Inclusion strategy to increase the number of ethnic minority colleagues at all grades, but especially at senior leadership levels.

- Develop with others our approach to collecting ethnicity data, so we can continue to review how our processes affect practices that are ethnic minority-led.

Introduction

We are the Care Quality Commission (CQC). We monitor, inspect and regulate services, including GP providers, to make sure they meet fundamental standards of quality and safety. We publish findings, including performance ratings, to help people choose care.

We are committed to being a fair regulator that delivers equality in our regulatory approach, driven by people’s needs and experiences and enabling health and care services and local systems to improve.

This report presents the findings of our research carried out in 2021, in response to concerns that practices led by GPs of an ethnic minority background could receive less favourable regulatory outcomes from CQC compared with those led by GPs of a non-ethnic minority background.

We started an initial programme of work in February 2021 to investigate and respond to those concerns and see what further work is needed. This work was conducted at considerable pace to enable us to promptly investigate the concerns raised. Our focus has been on how our own regulatory approach affects ethnic minority-led GP practices and how we can support them in the future.

Background

The quality of care delivered by GP practices in England is generally of a high quality. As at 31 July 2021, of the 6,429 practices on our register that had been rated, 5% (317) were rated as outstanding, 90% (5,806) were rated as good, 4% (276) were rated as requires improvement and 0.5% (30) were rated as inadequate (CQC ratings charts in State of Care 2020/21).

Despite these overall high ratings, we have received concerns from the GP sector about unequal outcomes, particularly for ethnic minority-led practices. These had been discussed in the media and were escalated formally when the Royal College of General Practitioners (RCGP) wrote to us in November 2020 with questions about the impact of our inspections on ethnic minority-led GP practices.

The correspondence highlighted a perception among members of RCGP’s council that ethnic minority-led GP practices received poorer ratings than their non-ethnic minority-led counterparts and were treated less favourably in CQC inspections. The RCGP asked us to work together to ensure transparency and involvement of ethnic minority GPs. At the time the letter was received, we had already started work to explore and review the literature relating to ethnic minority GPs, to understand the context and to help determine the scope of further research.

We are not alone in receiving concerns about differences in regulatory outcomes. Similar concerns have also been raised with other health and care regulators, such as the General Medical Council in Fair to refer? (2019), the Nursing and Midwifery Council’s Ambitious for Change (2020) and the General Pharmaceutical Council’s Managing concerns about pharmacy professionals: our strategy for change 2021-2026 (2021).

Our commitment to reducing health inequalities

The programme of work set out in this report is underpinned by our commitment to helping to reduce inequalities in people’s outcomes from their care and treatment, and to drive improvement for people who need it most.

Our strategy and our Equality Objectives for 2021-25 aim to help deliver equality not only for people who use health and social care services, but also for people working in health and social care, for the health and care providers that we regulate, and for our own workforce. Our ambition is to ensure that our regulation is driven by people’s needs and experiences, and to enable health and care services and local systems to access support to help improve the quality of care.

In our regulation, we expect to see that all people receive the same quality of care, whatever their circumstances. To assess this, we need to consider not only the outcomes for people, but also when a GP practice improves outcomes, for example in areas of deprivation. In this way we will drive improvement to reduce inequalities in outcomes.

The context for this research

We set out to discover the extent of any inequalities in our regulatory outcomes for ethnic minority-led GP practices. As a starting point, we carried out a literature review to understand the context, to help determine the scope, and to develop our research questions.

It is important to note that comprehensive ethnicity data for GPs is not available. For example, the ethnicity of approximately 11% of the GPs on the General Medical Council’s (GMC’s) GP Register is not known. The literature we reviewed has often taken the place of primary medical qualification as a proxy indicator for ethnicity, as this data is readily available – but this has substantial weaknesses, given that many ethnic minority GPs will have received their primary medical qualification in the UK.

Taking this key limitation into account, the literature provides many possible explanations for why there may be a disparity in regulatory outcomes for ethnic minority-led GP practices compared with non-ethnic minority-led GP practices. These include factors that relate to the individual circumstances of GPs from an ethnic minority background and those that relate to their practice environment and the wider system in which they work.

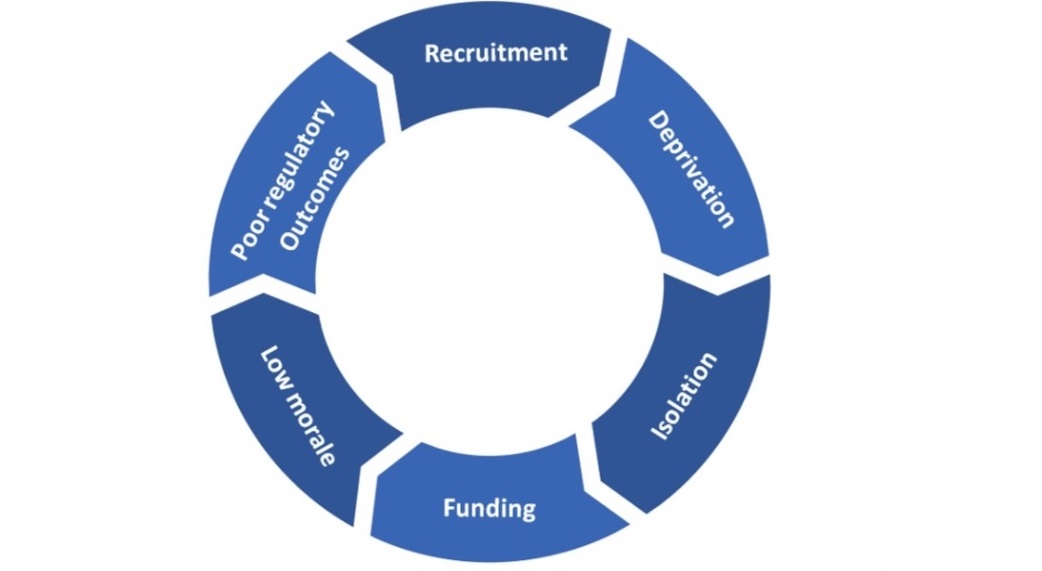

When combined, these factors present as a continuous cycle of inequality (figure 1). Although many of these factors can affect practices led by GPs of all ethnicities, they often disproportionately affect ethnic minority-led GP practices.

Figure 1: The Cycle of Inequality

Stigwood, A, 2020

The cycle of inequality starts with recruitment. Literature has previously shown that NHS recruitment processes disproportionately favoured White applicants (The snowy white peaks of the NHS: a survey of discrimination in governance and leadership and the potential impact on patient care in London and England, Kline, 2014), and that inequalities in recruitment continue.

Closely linked to recruitment is the issue of deprivation. Literature has shown that non-UK qualified GPs consistently work in practices in more deprived areas, working with patients who are in poorer health. These GPs are also older and work longer hours (The potential impact of Brexit and immigration policies on the GP workforce in England, Esmail, 2017). The Health Foundation’s briefing Level or not? (Fisher and others, 2020) found that GPs working in areas serving the most deprived patients are responsible for the care of approximately 10% more patients than those located in the most affluent areas. In terms of quality, this briefing also found that practices in deprived areas were more likely to be rated as inadequate or requires improvement.

In the cycle of inequality, after deprivation follows isolation. Non-UK qualified GPs are often recruited into areas of deprivation, where they are more likely to be working in isolation (Esmail, 2017) and operating single-handedly. The General Medical Council’s 2019 report Fair to refer? found that ethnic minority GPs working in professional isolation felt overworked, with little time to promote their own development or that of the wider health system.

Furthermore, the 2020 briefing from the Health Foundation Level or not? (Fisher and others) found that these practices are more likely to receive less funding as, once adjusted for workload, practices in deprived areas receive around 7% less overall funding for each patient (when adjusted for need) than those in more affluent areas.

After funding, the cycle of inequality leads to the morale of GPs from an ethnic minority background. While we did not identify any studies that specifically considered the mental health and morale of these GPs, more general studies have indicated that this could be of concern. The 2019 study GP retention in the UK: a worsening crisis (Owen and others) found that GPs identified complexity of patients, heavy workloads and inadequate funding to be key issues in general practice, which led to stress and exhaustion. These factors often apply disproportionately to non-UK qualified GPs who are more often working in areas of deprivation, which may in turn unduly affect their mental health and morale.

Finally, the cycle comes to regulatory outcomes. These include decisions by regulators about ethnic minority GPs and ethnic minority-led GP providers. In Fair to refer?, the GMC identified that it received a disproportionate number of complaints about non-UK qualified and ethnic minority doctors from their employers compared with non-ethnic minority doctors and doctors who qualified in the UK. This is significant as complaints made by employers are more likely to be investigated. Between 2012 and 2017, employers complained about 1.1% of Black and minority ethnic doctors to the GMC, compared with 0.5% of White doctors.

Literature shows that recruitment can be impeded when practices experience adverse CQC outcomes (CQC inspections: unintended consequences of being placed in special measures, Rendel S, Crawley H, & Ballard T, 2015). Poor regulatory outcomes can deter potential recruits from applying to a particular practice, and the cycle of inequality continues.

What we did

Research questions

The research for this work was based on the overall question:

Does CQC’s approach for regulating general practice have a differential impact on ethnic minority-led GP practices compared with non-ethnic minority-led GP practices? If so, what are the factors associated with these differences and what changes could help to promote equity of CQC’s regulation?

This main question guided our approach. To provide the framework we needed for the work, we split it into three separate parts:

- Is there a difference in ratings, outcomes or experiences between ethnic minority-led GP practices and non-ethnic minority-led GP practices?

- What are the factors that may be associated with differences in ratings, outcomes or experiences?

- What improvement could CQC consider to help promote equity in ratings, outcomes and experiences?

Defining an ethnic minority-led GP practice

As a starting point, we needed to identify practices that are led by GPs from an ethnic minority background. CQC registers and regulates ‘providers’ of GP services. The ‘provider’ may be an individual GP, a partnership of GPs, or an organisation or company. For this work, we excluded parent or corporate companies as we wanted to determine who was providing hands-on leadership at a practice level. We refer to ‘providers’ when we are talking about the legal entity and ‘practices’ when we are discussing the location where the GP services are being delivered.

Identifying ethnic minority-led GP practices presented difficulties for a number of reasons:

- There is no agreed system-wide definition of an ethnic minority-led practice.

- We do not collect data on the ethnicity of the provider and there is no mandatory data collection; this is only collected on a voluntary basis by some other organisations, for example the General Medical Council.

- Some practices may consider their leadership as being wider than the lead GPs or partners.

We consulted with our external stakeholders to develop a definition of an ethnic minority-led GP practice to apply to our research. The agreed definition was:

Where 50% or more of the GP partners are of an ethnic minority background

or

The individual provider or single-handed GP is of an ethnic minority background

To enable us to use this definition, we considered an ethnic minority background to be where a person’s ethnicity is from all ethnic groups except the White British group. (Ethnic minorities therefore include White minorities, such as Gypsy, Roma and Irish Traveller groups.)

We also gave practices the opportunity to self-identify as ethnic minority-led if they felt that they were ethnic minority-led but that our definition did not accurately reflect their leadership.

We carried out a survey of all GP practices (providers) registered with us (6,011). There were 771 responses to the survey, a response rate of 13%. Of the 771 respondents, 51% (390) reported that they met our definition of an ethnic minority-led practice. A further 3% (20) of practices reported that they considered themselves to be ethnic minority-led, but they did not meet our definition. Forty-five per cent of practices responded that they are non-ethnic minority-led (349), with the remaining 12 practices stating, ‘I don’t know’, ‘does not meet definition, practice is part of a company’ or ‘prefer not to say’.

As the majority of practices were able to identify as ethnic-minority-led or non-ethnic minority-led, this gave us assurance in our definition. The 20 practices who considered themselves to be ethnic minority-led but did not meet our definition gave a number of reasons why (figure 2).

Figure 2: Breakdown of reasons why practices did not fit our definition

| Reasons why practices did not meet our definition of ethnic minority-led | Count |

|---|---|

|

We define our practice leadership as being wider than the partners |

7 |

| We define our practice leadership as being only certain partnership members (not all members) | 1 |

| We define our leadership using a different percentage cut-off of partners from an ethnic minority background (less than CQC's definition of 50% of partners being ethnic minority background meaning a practice is ethnic minority-led) | 6 |

| Other | 5 |

| No reason given | 1 |

| Total | 20 |

Methodology

We used a series of quantitative and qualitative methods in this research to answer our research questions. These were targeted both at external stakeholders, GP providers, and internal stakeholders within CQC.

Quantitative methods

Surveys

We designed two surveys: one was to understand the experiences of GP providers, where the focus was on the experience of their most recent inspection of a practice (a number of GP providers have more than one practice location); the other was a survey of our inspectors.

We designed and tested the GP practice survey in consultation with our national professional advisors, subject experts, practising GPs and GP trainees. We sent this to all CQC-registered GP providers (6,011 providers) using the email address that was registered with CQC. The email included a unique link so that we only received one response for each provider. The survey was sent on 6 August and closed on 31 August 2021. We received 771 responses, which is a response rate of 13%.

The survey of CQC inspectors was designed and tested in consultation with the Inspectors’ Reference Group (a group of inspectors who met regularly to discuss the internal CQC elements of this project). We emailed this to all GP inspectors in our Primary Medical Services (PMS) directorate (169 inspectors). A unique link ensured that we only received one response from each inspector. The survey was sent on 31 August and closed on 10 September 2021. We received responses from 57 inspectors, which is a response rate of 34%.

A team of senior analysts and analyst team leaders in our Provider Analytics team and Data Science and Statistics team analysed the data. All the data analyses from the two surveys were quality assured by separate senior analysts and analyst team leaders.

Ethnicity of CQC staff

Electronic staff records hold the personal details of each CQC employee, including self-reported ethnicity data. CQC’s People directorate provided self-reported ethnicity data for a total of 3,129 employees during August 2021. We analysed this data to investigate the diversity at different levels of seniority and within different teams. For CQC’s Primary Medical Services (PMS) directorate, we explored diversity within the GP inspection teams and within the roles that involve making decisions about ratings.

We also reviewed the ethnicity of specialist advisors who provide specialist support for inspections of GP practices, and of bank inspectors who are non-permanent staff engaged with CQC to support inspection work when needed.

CQC’s People directorate provided quality-assured data analysis to the Intelligence teams, suppressing low numbers to ensure people could not be identified.

Qualitative methods

Online community

We commissioned Versiti, an independent research company, to speak to lead GPs from ethnic minority backgrounds about their experiences. We jointly developed discussion guides to use in an online research community, where participants were able to interact with tasks and questions over five days. The aim of the online community was to gain insight into GPs’ lived experiences of CQC regulation, and the results should not be treated as representative for all GPs.

Versiti moderated a five-day online research community of 36 GPs from diverse ethnic minority backgrounds. Of these 36 GPs, 30 self-identified as lead GPs, two did not disclose whether they were lead GPs, and four did not consider themselves to be lead GPs. All participants had experiences of CQC inspections. It was necessary to include these non-lead GPs to ensure that we captured the feedback of a more diverse group of GPs. All the GPs had volunteered to participate in this project. All but one of the GPs had experienced a CQC inspection in the last five years and worked in a mix of urban, suburban and rural areas across England. The sample included male and female lead GPs from a variety of ethnic minority backgrounds (all GP participants identified as being from an ethnic minority background).

The GPs were asked to log in to a controlled website and participate in tasks addressing five overall topics over five days. An online moderator from Versiti posted daily tasks and questions and probed if necessary. Our analysts and the leads for this programme were able to log on and observe the discussions throughout the data collection period and prompt the moderator to follow up on any comments.

Versiti reviewed and structured the data according to themes. They worked with our qualitative analysis team to structure the findings in a report template and produced a report of the qualitative content analysis. Our qualitative analysts reviewed the final report from Versiti to check the clarity and whether the findings were based on evidence from the online community. They shared and discussed feedback with Versiti.

Focus groups and interviews

We used focus groups and interviews to understand the experiences of CQC inspectors, inspection managers and GP specialist advisors. Eight inspectors, four inspection managers and four GP specialist advisors were included. The qualitative analysis team decided on the sample size based on a number of criteria including, but not limited to, the objective for the qualitative research, how large the pool of potential participants was, and how practical it was to recruit a given number of participants in a limited timeframe. The sample size was appropriate for the purpose of this workstream, as the collected evidence was sufficient to address the research question.

We relied on inspectors and inspection managers to volunteer to take part and promoted the work through our internal networking platform and through other staff networks. Specialist advisors received a message through a bulletin, and we emailed 80 specialist advisors who had recently been on an inspection.

We collected data from the focus groups and interviews in August and September 2021, using discussion guides that reflected the research questions. Senior analysts in our qualitative team recorded and transcribed conversations and all discussions were facilitated by either an analyst team leader or a senior analyst.

Our qualitative analysts coded the content of transcripts. The team had regular analytical discussions to report on emerging findings and link findings from different questions into a narrative. This was inductive (data driven) thematic analysis. The team checked the final report to ensure that findings were based on evidence and that it included important findings. Examples and quotes were also checked for accuracy.

Review of our regulatory methods and practice

We reviewed our regulatory methods and how we apply them in practice, to investigate whether there might be opportunities to address any direct conscious or unconscious bias based on ethnicity as well as indirect factors such as deprivation. This work was undertaken by colleagues in our Policy team.

We shared our early findings with senior leaders and decision makers within CQC in a workshop. These senior leaders sit on quality assurance panels to ensure consistency and fairness in our ratings. We held this workshop to give context to how the methodology was developed and to see whether participants could identify any areas within our methodology that could be vulnerable to bias.

Decision making processes

In some instances, for example when a draft report indicates an overall rating of inadequate, that report must be reviewed by a quality assurance panel to confirm the ratings and ensure consistency in decision making.

When we send a draft inspection report to a provider, we ask them to check the factual accuracy and completeness of the information that we used to reach our judgements and ratings.

When we are considering whether enforcement action is required, we hold a management review meeting with inspectors, inspection managers, senior colleagues and experts to decide next steps in terms of regulatory action.

We identified 30 GP practices that met both of the following criteria:

- They had been asked to check the factual accuracy in the draft inspection report.

- We had discussed them at a management review meeting.

It was not necessary for the inspection report to have been through quality assurance panel to be included, but a number of them had.

This meant that we could look across our processes to see how our methods were applied to different GP practices and to compare ethnic minority-led practices with those that were not ethnic minority-led.

We determined whether these practices were likely to meet our definition of ‘ethnic minority-led’. As we anticipated that we would not be able to identify the ethnicity of the practice from data alone, we invited each practice to self-identify.

We contacted 30 practices. Eight practices responded – five practices confirmed that they identified as ethnic minority-led and three confirmed that they identified as non-ethnic minority-led. One further practice informed us that it was in the process of de-registering, so we discarded it from the sample. We do not know the ethnicity of the practices that did not respond. However, if we used the place of primary qualification as a proxy indicator for these practices, 11 additional practices would meet the definition of being ethnic minority-led.

We were unable to classify the remaining practices, which meant that, in total, 16 practices either self-identified as being ethnic minority-led and/or had a majority of partners who qualified outside the UK, and 14 practices did not respond to our request to self-identify or meet the proxy indicator.

We sent 10 of the 30 inspection reports to National Panel (the highest level in CQC’s quality assurance process, which aims to provide an independent objective review of reports and promote consistency in judgements across inspections). Seven out of the 10 reports were for providers that had self-identified as being ethnic minority-led or had a majority of partners who qualified outside the UK.

We reviewed the data to identify any themes that may have indicated issues in how we apply our methods, for example consistency or perceptions around our decision making. We reviewed changes in our guidance and our approach to inspection to understand how they may have affected outcomes or decisions made about practices.

Review of complaints

Our Complaints team reviewed complaints received from NHS GP practices from April 2016 to September 2021 (167 complaints). Each complaint was reviewed to identify any themes specifically relating to bias, discrimination, racism or any other protected equality characteristics. We carried out an in-depth detailed review of five complaints as well as how we responded to them. Of the five complaints, one was upheld, two were partially upheld and two were not upheld, at the time our Complaints team handled them.

Engagement

We wanted our research and findings to be as open and transparent as possible, to make sure we were addressing the important questions that needed to be answered.

At the outset, we publicised our project through our online Citizenlab platform, to explain what we were doing, why we were doing it and our plans to progress the work. We also promoted the GP practice survey through our provider bulletin, and we published internal and external blogs, podcasts and bulletins to keep people informed and tell people how to contact us if they wanted to share their views. We also spoke at CQC’s GP Reference Group, which includes organisations such as primary care networks, NHS Clinical Commissioners and the Digital Healthcare Council.

External advisory group

At the beginning of this programme of work, we identified key representative organisations that were focused on the inequalities faced by GPs from an ethnic minority background. We invited their members to review and comment on our work, from scoping through to fieldwork. These people formed our external advisory group (EAG), who were able to provide expertise and advice as the project progressed and met every month during the project.

System partners

A ‘round table’ of external organisations, regulators and arm’s length bodies – a sub-group of the Primary Care Quality Board – was developed to progress collaborative working across the health system in reducing inequalities faced by ethnic minority-led GPs. The terms of reference for this group are set out in appendix B. The group met monthly throughout the project. The members include organisations with a role in improving the quality of primary care and/or supporting primary care providers and healthcare professionals in England, as well as organisations that represent ethnic minority providers and healthcare professionals.

The initial purpose of this roundtable was to address the concerns in the primary care sector that ethnic minority-led GP practices are more likely to receive lower ratings from CQC and to explore the challenges that ethnic minority-led practices may disproportionately face in meeting their regulatory, legal or commissioning requirements. It has been developed further to progress collaborative working across the health and care sector to reduce inequalities for ethnic minority GPs and also to consider health inequalities.

Inspector's reference group

We developed a reference group of inspectors to support the internal CQC elements of the project, such as the survey of inspectors and our review of regulatory methods. We asked for volunteers through our staff bulletin and by email, and held regular meetings to gather feedback and support during the fieldwork stage. This was to ensure that we captured the expertise and experience from a wide range of inspection colleagues.

Subject matter experts

To help develop our methods and research questions for this programme of work, we consulted with experts in the field of inequalities in primary care, asking for their advice and support and updating them with our findings.

What we found

Research question 1: Is there a difference in ratings, outcomes or experiences between ethnic minority-led GP practices and non-ethnic minority-led GP practices?

To answer this question, we considered the following:

- Statistical modelling, to understand whether there is an association between the ethnicity of doctors working in a practice and CQC ratings after taking into account other factors that can be associated with ratings (for example, deprivation in the local area).

- Accounts from ethnic minority GPs, shared in the online research community.

- Results from the GP practice survey – in particular, any notable differences in the results from ethnic minority-led and non-ethnic minority-led GP practices.

- Views of CQC inspection teams, shared in interviews and forums and from the results of the inspector survey.

We have split our findings into several sub-questions.

Do ethnic minority-led practices have poorer ratings?

To establish whether there is a difference in our ratings of ethnic minority-led and non-ethnic minority-led GP practices after accounting for other factors that could affect ratings, we hoped to perform statistical modelling using data held by CQC about GP practices and their local area, and national indicators, as well as data held by the General Medical Council (GMC) about the demographics of registrant GPs.

However, the data that were available were not sufficiently complete to perform effective statistical modelling that would ensure that any conclusions were robust and based on good evidence.

Challenges included a lack of full ethnicity data for the majority of GP practices and not being able to match some GMC data to CQC-registered locations. This left a small sample size of around 20% of all rated GP practices (1,324) with full ethnicity data (this is 20% of all GP practices, rather than GP providers as some providers run more than one practice). In addition, the number of GP practices that were rated overall as requires improvement or inadequate was low (100 practices), making it unlikely that a model would be able to detect a relationship between the ethnicity of doctors working in a practice (or other factors) and ratings, even if such a relationship existed.

We also lacked consistent historical data for key variables, such as the health profile of the patient population, due to changes in data collection for the NHS GP Patient Survey in 2018. This meant we would have had low confidence in the results of the model. For example, if we found a relationship between the ethnicity of doctors and our ratings, we would not be able to rule out that this was because practices with a high proportion of ethnic minority doctors serve populations with a higher prevalence of long-term health conditions. For this reason, we were unable to fully answer the first part of this research question. See appendix A for more details of the statistical model.

In our GP inspector survey, we asked whether there were perceptions of difference in ratings:

- 37% (20/54) of inspectors disagreed that ethnic minority-led practices were more likely to have poorer ratings

- 37% (20/54) gave a neutral response

- 26% (14/54) agreed.

This highlights that the majority of inspectors either did not perceive there to be a difference in ratings between ethnic minority-led and non-ethnic minority-led practices or had no opinion.

However, the perceptions of inspectors were not echoed by ethnic minority-led GP providers. In the GP practice survey, ethnic minority-led GP providers perceived that they had a poorer inspection outcome based on their ethnicity: 31% (124/400) of ethnic minority-led practices agreed or strongly agreed that their inspection outcome was adversely affected by ethnicity, compared with only 0.3% (1/304) of non-ethnic minority-led practices. (Note: A small number of ethnic minority and non-ethnic minority respondents answered ‘not applicable’ for these survey questions and were removed from the denominators.)

Are ethnic minority-led practices more likely to be inspected?

As we could not complete statistical analysis, we were unable to report whether ethnic minority-led practices were more likely to be inspected. However, we did ask for views that are relevant for this question.

In our survey of inspectors, we asked them to rank the top three factors that were most likely to trigger an inspection outside of planned inspection frequencies for all GP practices (which were based on ratings). These were:

- whistleblowing concerns 51% (29/57)

- information of concern raised by the CCG 16% (9/57)

- deterioration in performance of key indicators (QOF, GP Patient Survey, Public Health) 14% (8/57).

Fifty-seven per cent (31/54) of inspectors disagreed that ethnic minority-led practices were more likely to have an inspection triggered by information of concern, although 13% (7/54) agreed and 30% (16/54) gave a neutral response.

Similarly, one inspection manager mentioned in a focus group that they could not think of anything specific that would single out ethnic minority-led GP practices. Rather, they explained that the frequency of inspections was based on previous ratings, risk, data and other information of concern.

Through the GP practice survey, we asked whether the most recent inspection was carried out through an on-site visit or completed off-site.

On-site inspection visits were carried out for:

- 61% (251/410) of ethnic minority-led practices

- 69% (242/349) of non-ethnic minority-led practices

The proportion of inspections that were completed off-site was almost the same for both:

- 26% (108/410) of ethnic minority-led practices

- 27% (93/349) of non-ethnic minority-led practices.

There was a bigger difference in inspections that were a mixture of on and off-site, although the numbers are small:

- 12% (49/410) of ethnic minority-led practices

- 3% (12/349) of non-ethnic minority-led practices.

This implies that there is no notable difference in the types of inspections CQC uses for ethnic minority-led and non-ethnic minority-led practices.

We usually visit practices with poorer ratings or where we are taking enforcement action more frequently than those rated as good or outstanding. We do not know definitively whether ethnic minority-led practices do indeed receive poorer regulatory outcomes. However, if we assume that ethnic minority-led practices are more likely to experience certain contextual factors (discussed under the headings of ‘external system factors’ and ‘internal practice factors’ in this report), which may be associated with poorer inspection outcomes, then it is conceivable that there is a perception of more frequent inspection. However, it is important to note that this is merely a hypothesis and further research would be needed to explore this issue further.

Do ethnic minority-led practices have a differential experience of the inspection process and outcomes?

Through our research, we heard about GPs’ experiences of our inspection process and outcomes in two ways:

- through the GP practice survey (targeted at all GP practices)

- through the online research community (which engaged only GPs from ethnic minority backgrounds).

Therefore, the findings from the online research community only reflect the lived experiences of ethnic minority GPs, and direct comparisons with White British GPs are not appropriate.

Online research community findings

The online research community consisted of 36 GPs from ethnic minority backgrounds. This found that many experienced CQC inspections as a ‘threat’ and a punitive process rather than an opportunity to review, learn and grow. Moreover, many of these GPs reported feeling panicked and anxious in anticipation of a CQC inspection and that the inspection itself felt intrusive.

When ethnic minority GPs in the online research community were asked about the outcomes of inspection, they felt their results were usually in line with their own expectations, but the outcomes of the inspections rarely added value to the work of the practice.

Some GPs participating in the online research community felt that the inspection outcomes were ‘harsh’ and ‘unfair’ and did not consider the realities faced by the practices and their populations.

“My biggest ‘headache’ is probably CQC and the threat of an inspection because my mind is drawn to one particular CQC inspection in which I thought we would do really well and we would get outstanding. However, we were grilled for almost 10 to 12 hours [...] and despite getting good, we were still criticised for bowel screening figures which I felt was unfair as we have no control over bowel screening.”

(Male, Pakistani, Midlands)

The majority of the GPs who participated in the online research community had concerns around racial discrimination leading to unfair treatment from regulators, including CQC. A consistent theme among most of the participants was a sense that regulators do not understand or appreciate the challenges that ethnic minority doctors face. Some felt that assumptions are made about what an ethnic minority-led practice is like, seeking information to confirm their low expectations and ignoring positive evidence, resulting in a ‘predetermined outcome’.

“Whenever anyone comes to see us from NHSE/CQC/CCG, I always get the impression they make a judgement on us based perhaps on many reasons. Demographics, our names, our population, our location perhaps? But that judgement/stereotype is usually changed once they talk to us. It always helps I feel to have an English accent.”

(Male, Pakistani, North West England)

GP practice survey findings

In the GP practice survey, we were able to identify some key differences in the reported experiences of ethnic minority-led practices and non-ethnic minority-led practices. These were:

- 38% (156/410) of ethnic minority-led practices, compared with 26% (92/349) of non-ethnic minority-led practices, reported that one or more GPs in their practice experienced an adverse impact on their mental health because of the inspection process. Response rates were similar when comparing practices that served in areas of deprivation with those that did not (35% (133/383) and 31% (116/373) respectively).

- 51% (210/410) of those who identified as ethnic minority-led, compared with 41% (142/349) of non-ethnic minority-led practices, experienced a negative impact on their personal and/or family life because of the inspection process. We found similar results in practices that served a socio-economically deprived population (47% or 181/383 were negatively affected). However, this is similar to practices serving predominately non-deprived areas, where 46% (171/373) were negatively affected.

- 23% (93/410) of respondents from ethnic minority-led practices, compared with 7% (24/349) of respondents from non-ethnic minority-led practices, reported adverse physical health problems because of the inspection process. Practices serving predominately socio-economically deprived populations were almost twice as likely to report experiencing adverse physical health problems because of the inspection process compared with those in non-deprived areas.

- 23% (93/410) of ethnic minority-led practices, compared with 7% (23/349) of non-ethnic minority-led practices, felt that there had been an increase in staff sickness because of the inspection process.

- When comparing practices, 52% (212/405) of ethnic minority-led practices agreed or strongly agreed that the final inspection report and rating accurately reflected their practice, compared with 65% (226/346) of non-ethnic minority led practices. A higher proportion of ethnic minority-led practices than non-ethnic minority led practices disagreed or strongly disagreed with the statement (31% (124/405) compared with 17% (60/346).

- 27% (109/410) of ethnic minority-led practices, compared with 14% (48/349) of non-ethnic minority-led practices, agreed or strongly agreed that patient care improved following inspection. Almost half of respondents (360/771) neither agreed nor disagreed that inspections improved the quality of patient care.

The view of CQC inspection teams

We spoke to CQC inspectors and inspection managers, and GP specialist advisors to ask them about their perceptions and experiences of inspecting and regulating ethnic minority-led GP practices. They emphasised that they felt the ethnicity of the provider did not play a direct role in their approach to inspection or regulation; we discuss this further in research questions 2 and 3.

Some CQC colleagues gave examples of where differences between the approaches of inspection teams could have led to different outcomes. We heard from a specialist advisor who said they thought some inspectors might go into a practice with preconceptions which, as a specialist advisor, were difficult for them to challenge. This aligned with some views expressed by ethnic minority GPs in the online research community, that some CQC inspectors may have predetermined views.

There were also positive examples of specialist advisors and inspectors supporting GP practices to give the right evidence, for example by rephrasing questions, asking for evidence differently and spending more time finding the right evidence.

These findings suggest that there is a potential for different outcomes and experiences across our inspection process. We discuss in further detail the potential factors contributing to these differences in research question 2.

Recap

Due to limitations in the data available to us from all partners in the system, we were unable to fully explore the nature of the relationship, or existence of any causal link, between ethnic minority-led GP practices and regulatory outcomes such as ratings and frequency of inspection.

The majority of CQC inspectors did not agree that ethnic minority-led practices were more likely to have an inspection triggered by information of concern. In the focus groups with inspection teams, some inspectors and inspection managers linked the frequency of inspections to a practice’s performance, for example if they were in special measures, and emphasised that the inspection methodology is based on risk. The GP practice survey also indicated that there is not a notable difference in the types of inspections CQC uses for ethnic minority-led and non-ethnic minority-led practices.

However, ethnic minority GPs’ experiences of CQC’s inspection process and outcomes appear to be poor. We heard in the online research community that ethnic minority GPs felt inspection outcomes can be “harsh” and “unfair”. Most also had concerns about racial discrimination in regulation leading to unfair treatment, and felt that CQC, among others, does not understand or appreciate the unique challenges that ethnic minority doctors face. Some felt that assumptions are made about what an ethnic minority-led practice is like, leading to inspectors seeking information to confirm their low expectations and ignore positive evidence, resulting in a “predetermined outcome”.

In the focus groups with inspection teams, inspection colleagues told us that many ethnic minority-led practices that they had inspected had been in special measures. This could possibly lead to an impression that ethnic minority-led practices are inspected more frequently overall. Practices in special measures are inspected more frequently than those with a rating of good, to ensure that risks are mitigated. This association of ethnic minority-led practices with practices in special measures may create some unconscious biases towards these types of practices.

While we were unable to compare these experiences against those of non-ethnic minority GPs, the GP practice survey highlighted that ethnic minority-led practices were more likely to report that GPs in their practice experienced adverse impacts on their physical and mental health, personal and/or family life, and that they had seen an increase in staff sickness as a result of the inspection process. Ethnic minority-led practices were more likely to report that they agreed or strongly agreed that their inspection outcome was adversely affected by ethnicity compared with non-ethnic minority-led practices. A higher proportion of ethnic minority-led practices than non-ethnic minority-led practices disagreed or strongly disagreed that the final inspection report and rating accurately reflected their practice.

However, the GP practice survey highlighted some positive impacts, namely that ethnic minority-led practices were more likely to report that quality of care improved following a CQC inspection.

Research question 2: What are the factors that may be associated with differences in ratings, outcomes or experiences?

In this section, we present our findings in relation to the factors that may influence inspection outcomes. These include ‘internal factors’ that are internal to the practice such as its characteristics and leadership, ‘external factors’ that relate to the wider healthcare system and ‘internal CQC factors’ that relate to CQC’s processes and methodology.

Factors internal to ethnic minority-led practices

We know from our literature review that non-UK qualified GPs tend to work in practices in higher areas of deprivation, where patients are in poorer health. GPs in these practices are responsible for more patients and more likely to be working in isolation or operating single-handedly. Many of these factors can contribute to differences in ratings, outcomes or experiences of CQC regulation.

Single-handed or individually led practices:

In our survey of GP practices, 19% (143/771) of respondents stated that their practice was single-handed or individually led at their most recent inspection. Of these, 85% (121/143) stated that their practice was ethnic minority-led.

We know from feedback received in the online community of ethnic minority GPs that inspections were perceived as especially problematic and burdensome for smaller practices that had reduced capacity to focus on regulatory compliance.

“It is a stressful, bureaucratic, draconian nightmare which is designed generically but doesn’t take into account the size of an organisation. It is difficult, challenging and unrealistic. It also is very time consuming and sometimes pedantic… Some of the [key questions] apply to large organisations, and [a] small GP practice with five staff would simply struggle to be able to comply.” (Male, Indian, London)

In our internal focus group and interviews with CQC inspectors, inspection managers and specialist advisors, several participants emphasised the challenge associated with small and single-handed GP practices. This was perceived as frequently disadvantaging ethnic minority-led GP practices. It was discussed that single-handed practices were more often professionally isolated, while also having limited time to undertake inspection-related activities.

“It's often smaller practices that are already suffering, quite isolated, already struggling to attend all the meetings in their CCGs and they are often very isolated.”

(CQC specialist advisor)

“[…] with the amount of reporting and stuff that they've got to do, single handers often struggle with the reporting of things, even if they have actually done them.”

(CQC inspector)

Therefore, although we found that respondents in the GP practice survey who identified as ethnic minority-led were more likely to be rated as requires improvement or inadequate (51/59 requires improvement, 8/9 inadequate were ethnic minority-led), this may reflect the higher proportion of single-handed ethnic minority-led practices that responded to our survey and the challenges associated with our inspection methodology for these types of practices.

Practice management and leadership:

Participants in the internal CQC focus group and interviews discussed several factors related to poor practice management or leadership, which could affect inspection outcomes. Many of these were associated with single-handed practices, which the literature and survey findings suggest may be disproportionately ethnic minority-led.

CQC’s management review meetings are meetings to consider and discuss next steps when risk is identified. In the review of 30 management review meetings, we found that seven were held owing to concerns with leadership. All seven of those practices were among those that had self-identified as being ethnic minority-led or had a majority of partners who qualified outside the UK.

One inspector noted that, in their experience, many single-handed practices were run by GPs who qualified before CQC began regulating the sector. Several CQC colleagues thought that some GPs may face challenges in achieving good inspection outcomes as they had spent much of their working life without CQC regulation. In comparison, the participants felt that more recently qualified GPs may be more aware of, and have a greater understanding of, the expectations of today’s primary care, including the expectations of CQC regulation.

“A lot of the single-handed GPs that we have, and [who] I've met on inspection, a lot of them would have been […] older GP[s] and I think that the demands of modern primary care are certainly very different to those when they started off.”

(CQC inspector)

Some focus group and interview participants discussed IT skills as an important factor associated with inspection outcomes. As one specialist advisor emphasised, a GP’s ability to access and present relevant data and evidence can potentially affect the inspection process.

“I think IT plays a big role as well because perhaps some of the doctors are older and less tech savvy and everything is based on IT. Even to the extent of our new modus operandum, we’re doing all the Teams calls, and if you're not very good with Teams then you can't present the evidence or present yourself as well as you need to. A lot of things might be on paper or might be there but are not done. But unless everything is organised in an IT way then it's difficult.”

(CQC specialist advisor)

A few participants in the focus groups discussed that a GP’s inability to provide evidence within the inspection was associated with poorer inspection outcomes even if the practice fulfilled their regulatory obligations. As one inspector explained, impressions regarding competence and management could be formed by the inspector where necessary evidence was not provided within the inspection. Single-handed GP practices were more often associated with the challenge of presenting information and evidence. One inspector noted that the inability to provide information and evidence within the inspection could not be excused.

“So, what I tend to see is that there are gaps in the evidence, and I think that comes back to [the] challenge [of demonstrating] the evidence. In all possibility, they are actually complying, but they don't have the time, they don't have the hands on deck to be able to prove their evidence. And that's not acceptable as an excuse for us.”

(CQC inspector)

Several participants in the focus groups and interviews discussed family members as often being involved with the running of single-handed ethnic minority-led practices. Family-run practices were found to be a further factor associated with inspection outcomes, where there was limited training in place for family members, meaning a practice may not be managed and monitored effectively.

Other challenges were found to be associated with family-run practices. For instance, we heard from some focus group participants that the established methods of working, and the close family connection of family-run practices, made it more challenging for inspectors to engage with the practice and make suggestions to support the practice where possible. However, examples were given of how family relationships can have a positive impact on inspection outcomes. We heard one example of how a family member joined a practice’s leadership team and was able to drive change and work with a CQC team to improve the services provided.

Participants emphasised that challenges associated with family-run practices might disproportionately affect ethnic minority-led providers. However, they did not think that ethnicity itself had an impact on inspection outcomes. Participants considered the issues associated with poor practice management and leadership as potentially affecting inspection outcomes.

It is important to highlight that these were the views of CQC inspection teams. Therefore, while these findings highlight some internal challenges for ethnic minority-led practices, they also shed light on some potentially preconceived ideas or unconscious biases about particular types of practices, which might disadvantage ethnic minority-led practices.

Factors external to ethnic minority-led practices

As discussed in the previous section, ethnic minority-led GP practices often work in environments that may pose additional challenges. In this section, we explore the relationship between the wider healthcare environment, the GP practice and CQC regulation.

Ethnic minority communities and levels of deprivation:

Most GPs from ethnic minority-led practices that we spoke to in the online research community said that they operated in areas with a high concentration of people from ethnic minority communities and with high levels of deprivation. They consistently reported challenges that they felt were different from, or more acute than, the national profile. GPs who participated highlighted that ethnic minority-led practices often struggled with patients with complex long-term health needs, such as cancer, diabetes, heart disease and mental ill-health. They also mentioned challenges of low staffing levels, barriers to accessing care, and being over-subscribed to deliver care.

“We have a much younger population compared to the CCG and nationally, and […] the majority of these patients have English as a second language. Our CCG as a whole has the second highest proportion nationally of [Black and Ethnic Minority] patients (I think). Our population is much more deprived with some of the highest incidences of [Serious Mental Illness], together with double the national prevalence of type 2 diabetes. A large proportion of our newly registered patients have only recently arrived in the UK, mainly from Romania, Afghanistan, Iraq and Iran. These patients have massively complex needs – either due to the patients not having access to healthcare for many years, mental health and physical health issues as a result of their traumatic experiences, poverty and different health beliefs due to cultural factors.”

(Male, Indian, London)

In our survey of GP practices, 65% (267/410) of practices that identified as ethnic minority-led stated that they served a socio-economically deprived population, compared with 32% (113/349) of non-ethnic minority-led practices.

We asked practices whether CQC reflected their challenging factors in their inspection and/or rating. A larger proportion of ethnic minority-led practices than non-ethnic minority-led practices found the socio-economic deprivation of the practice’s population to be a challenging factor. Of all the respondents, 45% did not feel that their most challenging factor was reflected in their inspection/rating. For ethnic minority-led practices, this proportion was 52% (199/382), whereas for non-ethnic minority-led practices it was 38% (119/314). Note: respondents who answered ‘don’t know’ were removed from the analysis.

In our survey of CQC inspectors, the 57 respondents identified the top three factors most likely to pose a challenge to all GP practices as: socio-economic deprivation, low GP-to-patient ratio, and geographical considerations (figure 3). When discussed further in focus groups and interviews, colleagues noted that socio-economic deprivation levels within patient communities influenced the ability of GPs to achieve national targets considered by CQC.

“It's complicated because you can't just say all ethnic-background providers work in deprived areas, because that's not true. But, with practices in areas with high levels of deprivation, and I wouldn't at all equate these with being led by ethnic minority background GPs, but often they are […] they have very different patient populations with challenges […] they will never achieve the kind of percentages on monitoring data stats that we look at. They can try as hard as they like.”

(CQC inspector)

Figure 3: Comparison of responses between respondents in the GP practice survey and CQC inspector survey: What are the top five challenges faced by GP practices?

| GP practice survey: Responses from ethnic minority-led practices | Inspector survey: Overall results | |

|---|---|---|

| Challenge 1 | Patient expectations that cannot be met due to constraints | Socio-economic deprivation of the practice’s population |

| Challenge 2 | Complexity of patients’ health and communication needs | Low GP-to-patient ratio |

| Challenge 3 | Socio-economic deprivation of the practice's population | Geographical considerations (inner-city, remote, coastal, rural etc) |

| Challenge 4 | Direct effects of the COVID-19 pandemic on provision of care |

Complexity of patients’ health and communication needs Inadequate funding Professional isolation Recruitment and/or retention of GPs |

| Challenge 5 | Inadequate funding | Direct effects of the COVID-19 pandemic on the provision of care |

In focus groups, some inspectors and specialist advisors strongly noted that there was limited recognition within CQC’s methodology, including quality assurance panels, of the disadvantage of the surrounding contexts in which these practices exist. Rather, these participants emphasised that CQC’s inspection methodology does not sufficiently consider surrounding contexts, noting this as a challenge to achieving good inspection outcomes and discussing practices as being penalised for not achieving similar outcomes to practices with very different contexts and patient communities.

“I think deprivation is an important factor. It's really not taken into account in any way, shape or form, and the great difficulties that have to be undertaken due to that, and it's just assumed that all the outcomes will be perfectly as good as other areas.”

(CQC specialist advisor)

One inspector did note that while deprivation may be a negative factor to some practices’ inspection outcomes, they had had experience of inspecting flourishing practices within similar contexts.

“You know, I've also been to some practices where they've been in a high deprivation area, but actually been achieving well, so it's not always the case.”

(CQC inspector)

Workload and recruitment of staff:

We know that patients in areas of high deprivation tend to have poorer health and more complex needs. Often, these patients need more care from GPs.

Most of the GPs in our online research community highlighted an increase in demand for their services, especially in relation to COVID-19 and delays in secondary care. GPs felt that this was expected of them without any improvement in resourcing. This was further exacerbated by challenges in recruiting and retaining staff, particularly in practices that were working in areas of deprivation with large proportions of patients who were from ethnic minority backgrounds.

“Recruitment has always been difficult. As we are on the fringes of a city, rarely get more than one applicant when we advertise for doctors or clinical staff. In terms of admin staff, there has been a large turnaround of staff in the recent past. Many have left due to the attitude of patients towards them. [...] We have been short 1.5 full time equivalent GP for 2 years but having problems recruiting. The practice has hired paramedics and pharmacist to help with workload but we are short on doctor appointments.”

(Female, Arab, London)

Literature shows that recruitment may be impeded when practices experience adverse CQC outcomes (Rendel S, Crawley H, & Ballard T 2015). In our GP practice survey, we asked whether a CQC inspection had resulted in additional staff being recruited. Those that reported that staff were recruited after a CQC inspection were more likely to be ethnic minority-led. Ethnic minority-led practices were also more likely to experience challenges in recruiting staff. It is therefore difficult to understand whether these problems arise as a result of inspection activity or are pre-existing problems that are exacerbated by poorer ratings.

Additionally, some inspectors in our focus groups and interviews highlighted the impact of funding and investment as posing a challenge to recruitment. They discussed how single-handed practices often struggle to recruit enough clinical staff owing to their limited funding, and perceived single-handed practices as often not having enough staff to support practice demands. It was noted that this was compounded by practice staff often moving from single-handed practices to larger practices because of the greater training and development opportunities that larger practices could offer.

“It’s really difficult to get a good practice nurse […] there isn’t enough money to pay staff, and when you’re in a single-handed practice like that, there’s less money to pay staff to go do courses, to make sure their training is kept up to speed.”

(CQC Inspector)

Support from system bodies:

Support from external bodies within the health and care system can be helpful for GP practices in overcoming challenges and delivering high-quality care for all. However, we heard in the online research community that practices led by ethnic minority doctors often lacked leadership support from other bodies and suffered from low morale. Discussions with our CQC colleagues noted that support from the system, for example through CCGs and primary care networks (PCNs), varied between areas and often favoured larger practices and overlooked smaller single-handed practices.

“It may have an impact on regulation, but I think a lot [of] focus is on those big groups of GP practices who are […] high up in the PCN. Perhaps a smaller, sole provider gets lost or gets left behind. Although […] the onus is [actually] on the PCN to not leave them behind but specifically to put in support to make sure that they are coming up to regulatory standards.”

(CQC inspector)

This was echoed by ethnic minority GPs in our online community and, importantly, we heard an example from an inspector that GP ethnicity had an impact on the level of support received by practices.

Despite the likely benefits that system support would bring to practices that needed to make improvements, many respondents to the GP survey felt that there was no improvement in engagement with external bodies following an inspection, although this was not related to ethnicity. In our online community, ethnic minority GPs told us about their experiences.

“At times I feel I am really isolated and have to deal with several issues in isolation. We need more support from the CCG in terms of training and funding.”

(Female, Indian, North West)

“Since I relocated to the UK […], I have constantly experienced racism both direct and institutional. [outlines an instance of bullying and harassment by a member of practice staff] This issue was raised during CQC inspection. The advice was to ‘forget about it’ and move on. I was expecting the CQC to make a recommendation to NHSE.”